EPISODE 3: Healthcare Resiliency – Lessons from the Front Lines, Part 2, featuring Emily Brower, Trinity Health

“Trinity Health has always been very clear through the way that we deliver care, communicate, engage communities, that racism is a public health crisis … Many of the disparities in access, in treatment, in outcomes, many of those inequities were amplified with COVID. And that has led us to double-down on our advocacy for racial justice.” — Emily Brower, Senior Vice President of Clinical Integration and Physician Services at Trinity Health.

Host Aparna Higgins, Senior Policy Fellow at the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy and Senior Advisor to the LAN, interviews Emily Brower, Senior Vice President of Clinical Integration and Physician Services at Trinity Health and LAN Care Transformation Forum Co-chair. Emily shares how Trinity Health is responding to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of considering health equity in care delivery, and how APMs can support resiliency during public health emergencies.

Episode Q & A

(01:35) A year ago, the LAN launched the Healthcare Resiliency Framework in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that includes both short and long-term actions to build resiliency into our health care system. Trinity made a shared and individual commitments to that framework. Could you talk a little bit about some of the actions that Trinity Health System took in the short-term during the public health emergency to help create resilience?

Emily Brower:

I was so excited to be part of that work with the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. To recognize that the capabilities they had built in their population health enterprise were there and ready and able to respond to COVID, was a wonderful discovery. For Trinity Health, the years that we had invested in creating clinically integrated networks with really robust care coordination and support for populations attributed to the providers in that network through alternative payment models, that’s a very long description of our work. That investment we had made, we had built up strengths and muscle during that time that we were then able to pivot and flex and respond to the public health emergency in ways beyond even [what] we had anticipated.

And some of those were the way we responded clinically. If you think about the clinical team within a population health or ACO (accountable care organization) or CIN (clinically integrated network) enterprise, what that team does all the time is to look at a population of patients, understand their clinical conditions, prioritize them according to clinical risk, and then reach out to develop comprehensive patient-centered care plans. That’s sort of a broad general description. The ability to do that meant we could say your new attributed population of focus is people at risk of COVID. And so, we were able to take those same approaches of understanding a population—their clinical conditions, what put them at risk—for the impacts of COVID, and then respond in that same way that the team would do for any high-risk population. Reach out, make sure people understood their conditions, how to be safe, how to access care, make sure that—particularly early-on when many communities were asking people to stay at home and stay safe—to know how they could get home-delivered meals, home-delivered medications. It was this incredibly effective effort.

I’ve told this story before, but one of our care managers said she was doing the best care plan she had ever done because the people we were serving were very eager to know how to stay safe, were very eager for help—and in many cases—they were at home with a caregiver or family member who then was part of that conversation. It was really that comprehensive care plan that we often talk about in population health, but very detailed right down to all the ways that patient and family could stay safe and healthy. We had this incredible response [to COVID] that really leveraged the clinical teams.

The other area where the support that we provide for the provider network really shown is [that] we were able to have regular, and at some points during the public health emergency, even daily communications with the providers in our clinically integrated networks. Many of these are small practice, one, two independent practices in the neighborhoods that Trinity Health serves. Our ability to keep them informed as we were learning about COVID-19—who is at risk, the treatments, how to stay safe, all of that information that we as a large health system with infectious disease and a COVID response incident command and access to treatments and testing—we’re able to then include those independent providers showed the benefit of this work. We always talk about clinically integrated networks are a way for independent providers to move to a more sustainable and resilient practice and payment model, so that they can remain independent in the community. But this work during COVID, particularly in the early days when we were all learning, really showed the benefit of being part of that network and just being part of that whole system, having access to all that information and resources.

During a time when fee-for-service encounters just really dropped, and people were not seeking care, we were able to bring to those practices shared savings distributions and other dollars that come through the alternative payment models and for some of those practices, those were the dollars that kept them open…I’m struck by how this investment that we had made as a system because it’s so important to our mission paid off…The benefits in terms of being a more resilient network of providers and able to respond to the people in the community continues to be a really important story and support for this national change [to APMs] that we’re all involved in.

(09:43) How has your response to the LAN Resiliency Framework, in terms of the kind of models that you've implemented evolved due to the duration, intensity of the PHE (public health emergency)?

Emily Brower:

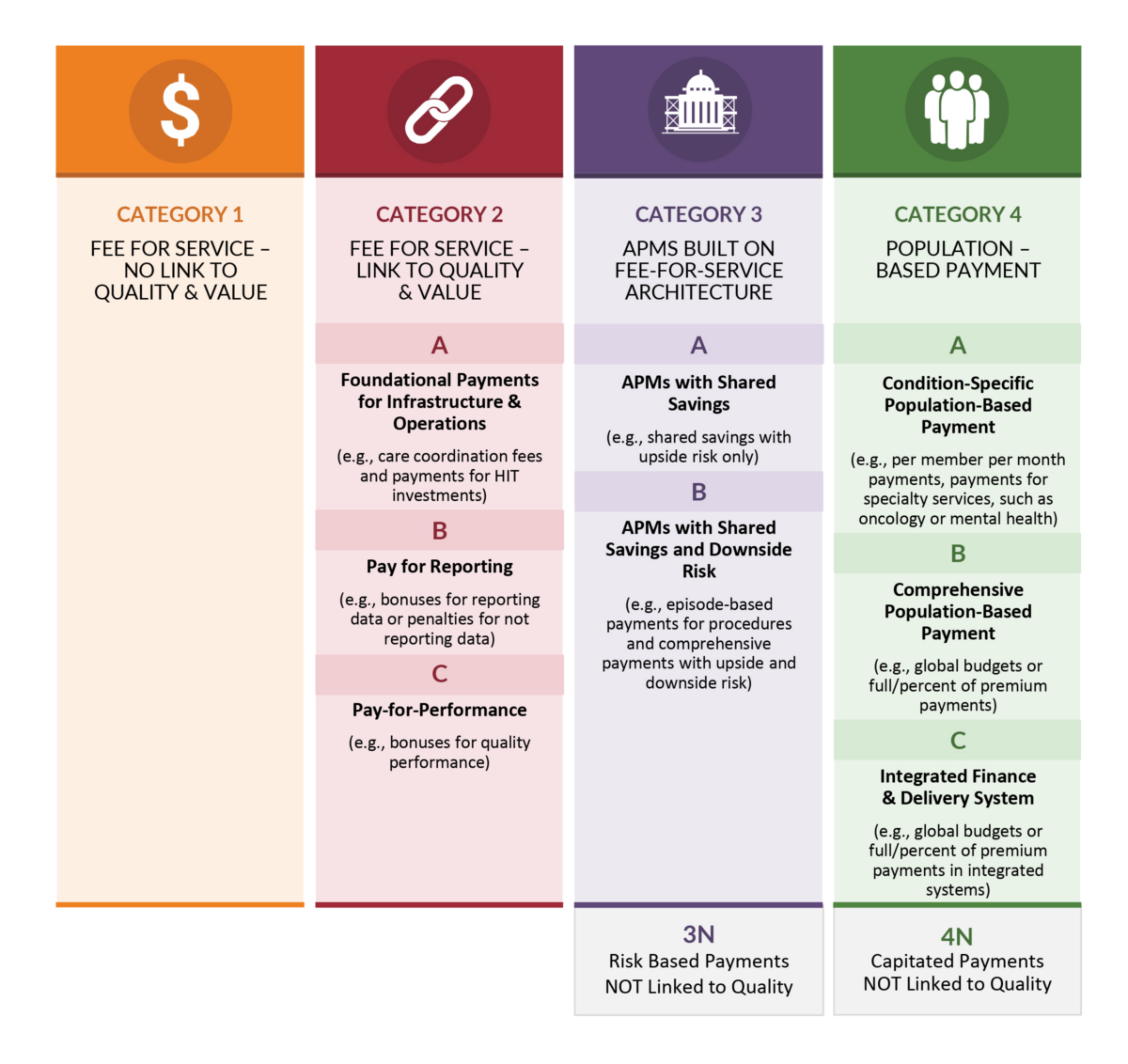

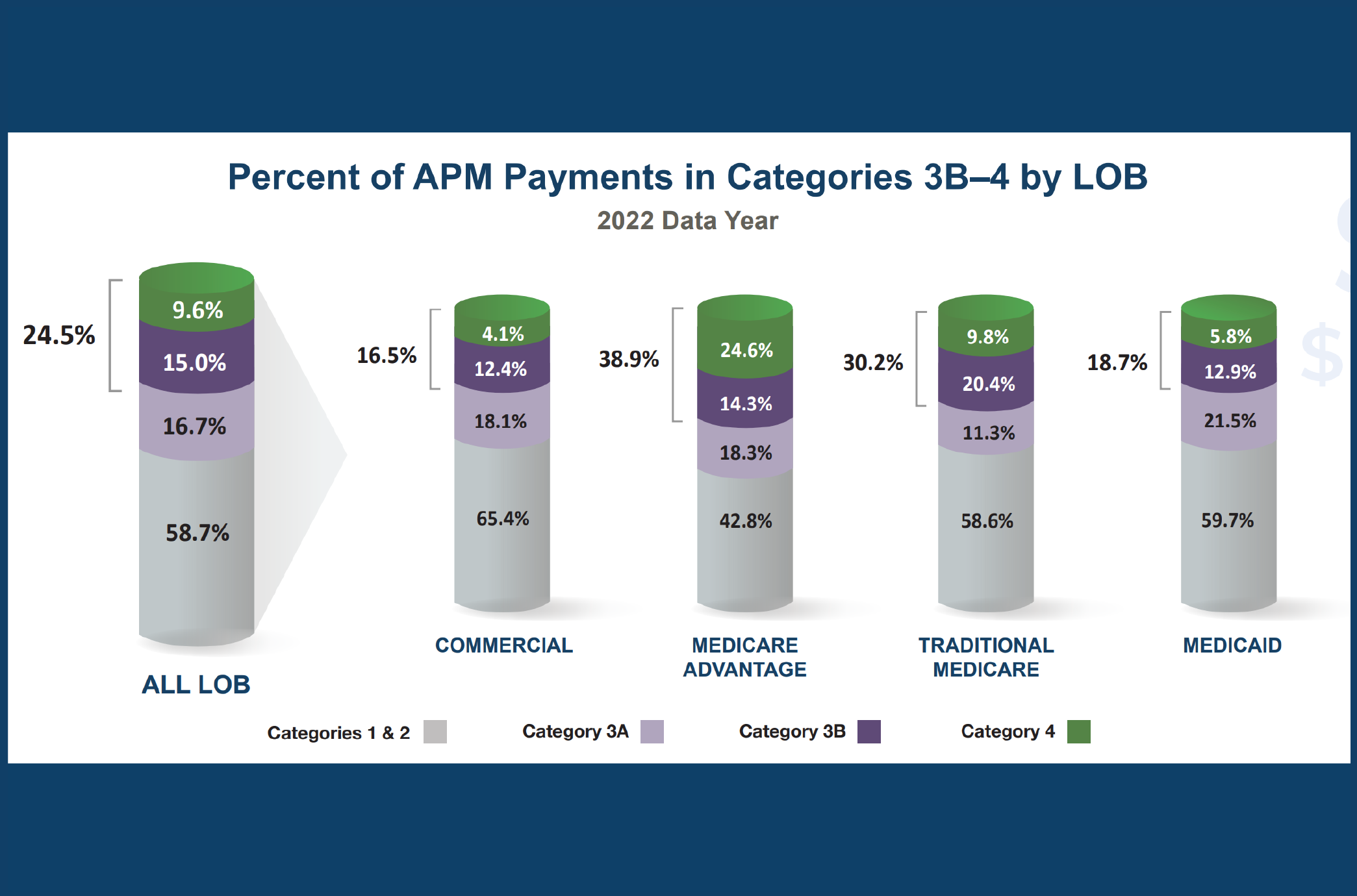

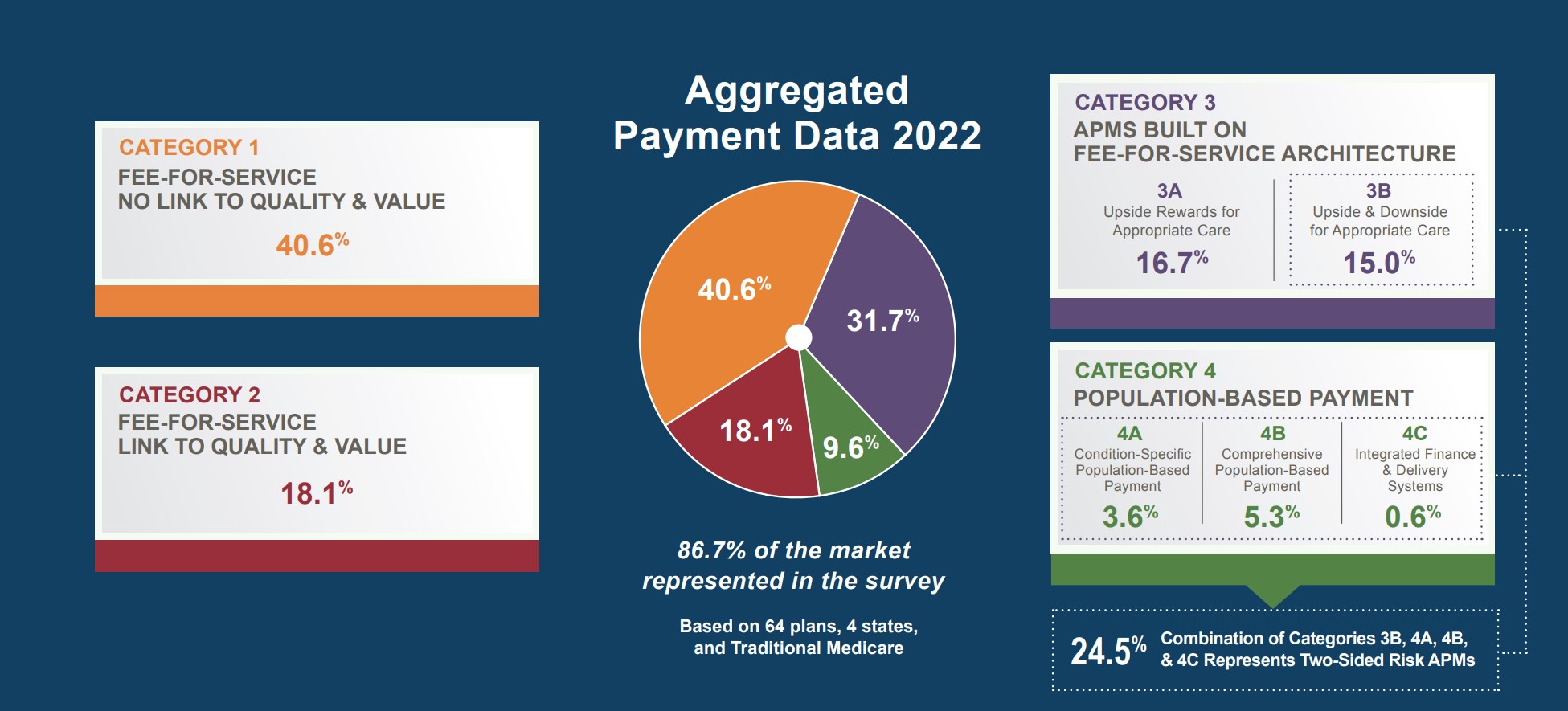

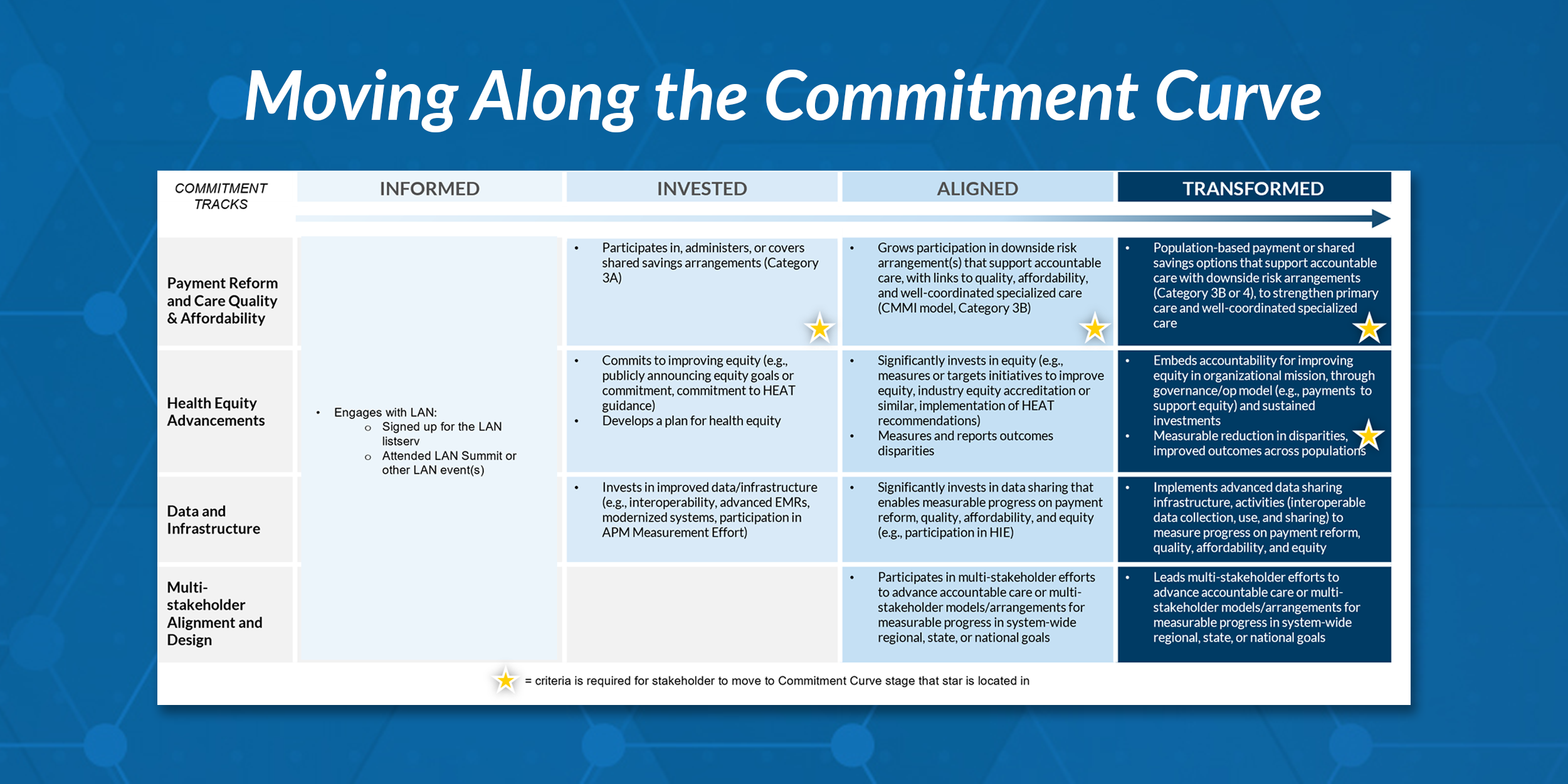

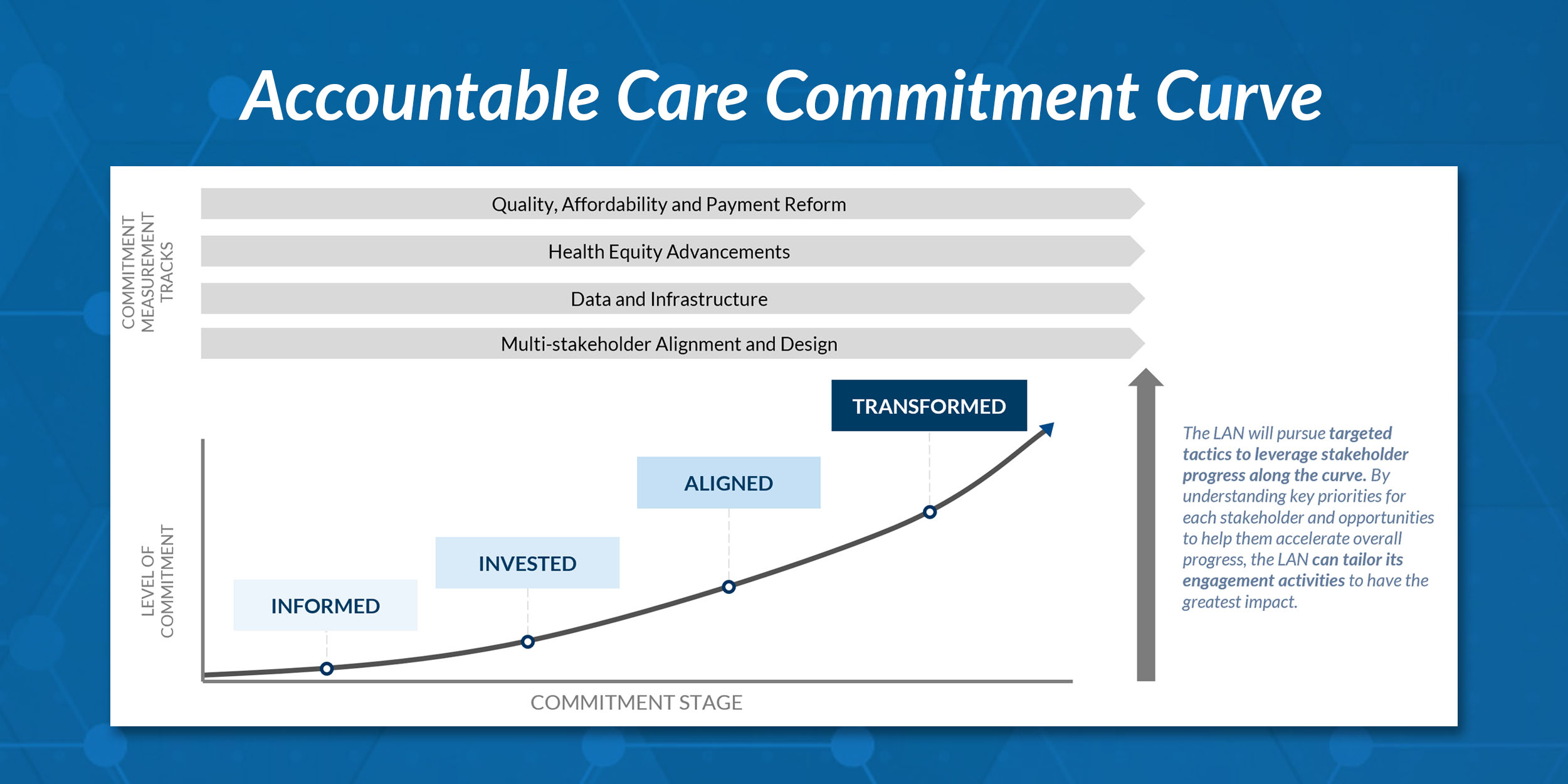

The experiences that I was just speaking of and our reflection on that, not just our own, but the work we did with the other members of the LAN, really emboldened us to accelerate our alternate payment model journey. If you think about the LAN taxonomy, we set very specific goals around increasing our participation, whether you look at contracts or covered lives, or people, providers in those total cost of care, population-based prospectively paid models. Moving along towards those category three and even more category four payment models. How can we get closer to the purchasers of care and meet the needs for the population that they are responsible for, whether it’s Medicare, a state Medicaid plan, or our commercial health plan partners, and directly with employers? how do we get closer to that full support of a population where we have even greater clinical and financial accountability? Through our recommitment back in October of 2020, we set very specific goals around that, more aggressive goals, and then we have been working hard to make that happen.

(12:53) We talk a lot about patient engagement, but your experience, speaks to a higher level of engagement. Can you talk about how we continue that, maintain that, and also ensure that people and their families are truly engaged in the care?

Emily Brower:

We, like others, moved fast and were super responsive and continue to be during the public health emergency. But I would say we collaborated even within our own integrated delivery system in ways that we had not before. And because of the speed of response that was needed, we just said ‘okay, what’s working here, spread it there. How do we grow this, do more of that?’ I would say more development, testing, and implementation of these small tests of change. And those have sustained. We are not going back to the way things were. I’ll use one example. We have Trinity Health, like many community-based health systems, and I think particularly you see this in Catholic health care, is the commitment to the health of the community. We had social care hubs to try and make it easier for people to access care in the community. We needed to quickly put all those pieces together. Like in the story I told earlier, our population healthcare managers who are reaching out to put together care plans and service plans for folks, they knew what are those community-based services that would close some of those gaps and engage them. That process of working through our community health and well-being teams and those social care hubs, that’s now just the way we work. There are many things that we did respond quickly to COVID that are now how we work… Both how we respond to the needs of our patients and communities. We have now just made that part of our overall response to any future need that that would come about.

(16:22) The PHE has laid bare many of the health disparities that currently exist within our health care system. Can you describe some of the actions Trinity has taken to address health disparities, particularly as it relates to COVID?

Emily Brower:

Trinity Health has always been very clear through the way that we deliver care, communicate, engage communities, that racism is a public health crisis…Many of the disparities in access in treatment in outcomes, many of those inequities were amplified with COVID. And that has led us to double-down on our advocacy for racial justice, [our] commitment to internally moving faster on our own journey for equitable compensation and talent, and the culture of inclusion that we strive to create within our organization and also for the people we serve. We’ve been accelerating our work on anti-racism training, diversity, equity, and inclusion work, including things like supply chain.

Our journey around addressing racism in health care, as part of our commitment to the “common good” falls under that general umbrella for us, that has just been accelerated as well. That really flows through how it showed up with COVID is really our accelerated response to the community, to access to care, to treatment, to vaccination. So just really [a] huge commitment to our communities in terms of increasing community-based vaccination, testing and making sure that communities of color have robust access to that. It’s been a very big piece of our commitment as an organization, as well as our COVID response.

(19:23) Can you talk a little bit about how some of these steps you have taken as it pertains specifically to COVID also translate into addressing health disparities more broadly outside of COVID, within your organization?

Emily Brower:

I’ll give you one example because there are many, but that ties back to what we were talking about earlier in terms of how rapidly we responded to COVID and what we learned from that, particularly in our work and integrating more of our community investments and community supports on those social care hubs. But we said ‘well, gee, what’s the population? How can we use this experience to inform our work in population health and alternative payment models? What can we take and move into some longer-term change? We know we have data on populations attributed to us. What do we know about health disparities and how they show up in some of our day-to-day work in caring for an attributed population?’ Across our organization, every team was choosing focused efforts where they could address health disparities and inequities. What we looked at is, well, in our Medicare ACO population, we do have some information about race and ethnicity. But we also found that in the populations who are dually enrolled for Medicare and Medicaid, there was actually a flag in the data that tells you, ‘This is the population.’ It’s not an exact match for race and ethnicity, we’re not saying that, but it was a population that we could look across the organizations because we have Medicare ACO’s in almost every market. We could say, what can we do to address disparities in that population in particular.

That’s where we did really a deep dive into typical population health metrics that we use to measure the impact we’re having on the health of a population. We dive into that and look for those disparities. What we found is that for those who are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, we found greater disparities and things like preventable ED (emergency department) visits, preventable hospitalization, some of our typical measures. So that’s an area where we decided to focus for this year.

We have a very specific set of clinical interventions that we do for that population, and we are looking in a very data-centered way. Are we moving the needle on reducing preventable hospitalizations? We use our ambulatory care sensitive condition admission measure. There’s also a measure in our ACO quality data that’s very similar. We said, ‘okay, we’re going to do something different for this population and then we’re going to measure the impact.’ For that population, when you dig into those ambulatory care sensitive conditions, you find tremendous disparities and things like poorly controlled diabetes or pick your chronic illness. That’s where we’re focusing. We’re doing that through adding to our usual care team, the community health worker. We have a whole initiative across all of Trinity Health to train, hire, deploy—as part of our population health care team—community health workers. We’ve had a lot of great experience with that and now it’s just the way we work for that population. To get closer to those underlying issues that show themselves through the data and then expect that we will be able to better meet the needs of that population with that additional member of the care team providing support and connection, and then the use of that whole network that we’ve developed through our social care hubs.

(25:13) Can you talk a little bit about the role APMs can play in intentionally addressing issues pertaining to health equity?

Emily Brower:

I think this is very much coming out of the experience that I was speaking about earlier, which is when you participate in alternative payment models that assign you a population of patients and say you, the providers, are now accountable for the clinical and financial outcomes and the experience of care for this population, what comes with that is data that helps you better understand the needs of that population. If that’s how the data comes to you for this population, and it often does, the set of encounters, all the diagnoses, and information that come with that, really help you to understand a population of patients in a much richer way than you would if you were only looking at your own encounter data. So, what you might have in your primary care practice, for example, because those are people you’re caring for.

Once you’ve got that full claims data set, and you can see all of the conditions that that group of patients or any one individual patient is being treated for, all the different providers who are providing their care, and all those points along the continuum, that just becomes a much more enriched understanding of a patient and a population of patients. It works really on two levels: the patient you’re focusing on, you now have a much more complete understanding of the care they are seeking, and the clinical conditions they have. On that patient level, it’s very enriched. At a population level, what that does for you is, I once had one of my clinical partners say, it’s sort of like doing a differential diagnosis on a population, like you can see for an entire population, where do we need to be focusing? Boy, am I seeing a lot of folks who are getting multiple admissions for congestive heart failure, for example, and that bubbles up into a pattern of care that then enables you to say, ‘I’m going to design a population-based intervention for that.’ It’s both that individual patient and the richer understanding of their care and their conditions, as well as being able to take that more integrated, systematic approach to redesigning care for a population.

(29:12) Trinity has been making these investments over multiple years and has been on this incredible journey in terms of advancing value. Based on your experience and lessons learned, what kind of advice or guidance would you give to other payers or providers who were contemplating this journey towards value-based care?

Emily Brower:

It’s a long road, is what I will say. I was talking to some friends of mine about, wow, it’s been 10 years since the Affordable Care Act and we’re still doing this blocking and tackling every day creating one more small bend in the cost curve, if you will. Did we think we were still going to be here? That the journey would be this long? I think many people thought this would happen much faster. So, stick-to-itiveness, patience— I’m not the most patient person. This is all about the long run, right? We see this in the results of, say, ACOs and those that achieve year-over-year improvements in quality and cost. Those are the ones who’ve been in it the longest. It’s the patience and stick-to-itiveness and being sure to find and call out those small bends, because they do add up over time to some pretty significant improvements in the care of a community or a population and making care more affordable. So, there’s that long-term horizon. We are very much in this for the long-term. Don’t lose hope. Stick with it.

The other is, I think the reason that Trinity Health has made this commitment over time is because it’s absolutely central to our mission. Trinity Health is really the leading health system in this work. If you look at the number of communities we serve, the number of people that are attributed to us, the number of people that we’re caring for through these population health models, the number of providers, and the success that we’ve had. That is absolutely because it is central to our mission to transform the health of the communities we serve. All of that is to say, it’s really important when you’re doing this kind of huge change, to be able to speak to how central it is to the mission and goals of the organization. We really keep that front and center of our organizational strategy, our work with our health plan partners. It really infuses through the organization, and it goes back to that we will be that healing, transforming presence in the communities we serve. It is just central to our mission. That’s why it has staying power. Because it is a long-term play. And so, it needs to be really core to the organization’s mission and values and vision.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models. Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices.

Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices. Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System.

Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System. Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities.

Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities. Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.