EPISODE 4: At the Intersection of Equity and APMs featuring Dr. Marshall Chin, HEAT Co-Chair

“It’s not just payment reform for payment reform’s sake… it’s payment reform that needs to support and incentivize those care transformations that holistically address a patient’s medical and social needs to advance health equity.” — Dr. Marshall Chin, University of Chicago

Host Aparna Higgins, senior policy fellow, Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke University and senior advisor to the LAN, interviews Dr. Marshall Chin, HEAT Co-Chair. Dr. Chin shares how APMs and other value-based payment models can contribute to and improve health equity. The conversation also delves into the issues of social determinants of health, incorporating health equity into APM plan design, and highlights some of the key points of the HEAT’s recently published guidance document, Advancing Health Equity through APMs.

Episode Q & A

(03:02) The HEAT recently released its first publication, a guidance document entitled Advancing Health Equity through APMs. So, as co-chair, can you tell us a little bit more about how the document came about and what it hopes to achieve?

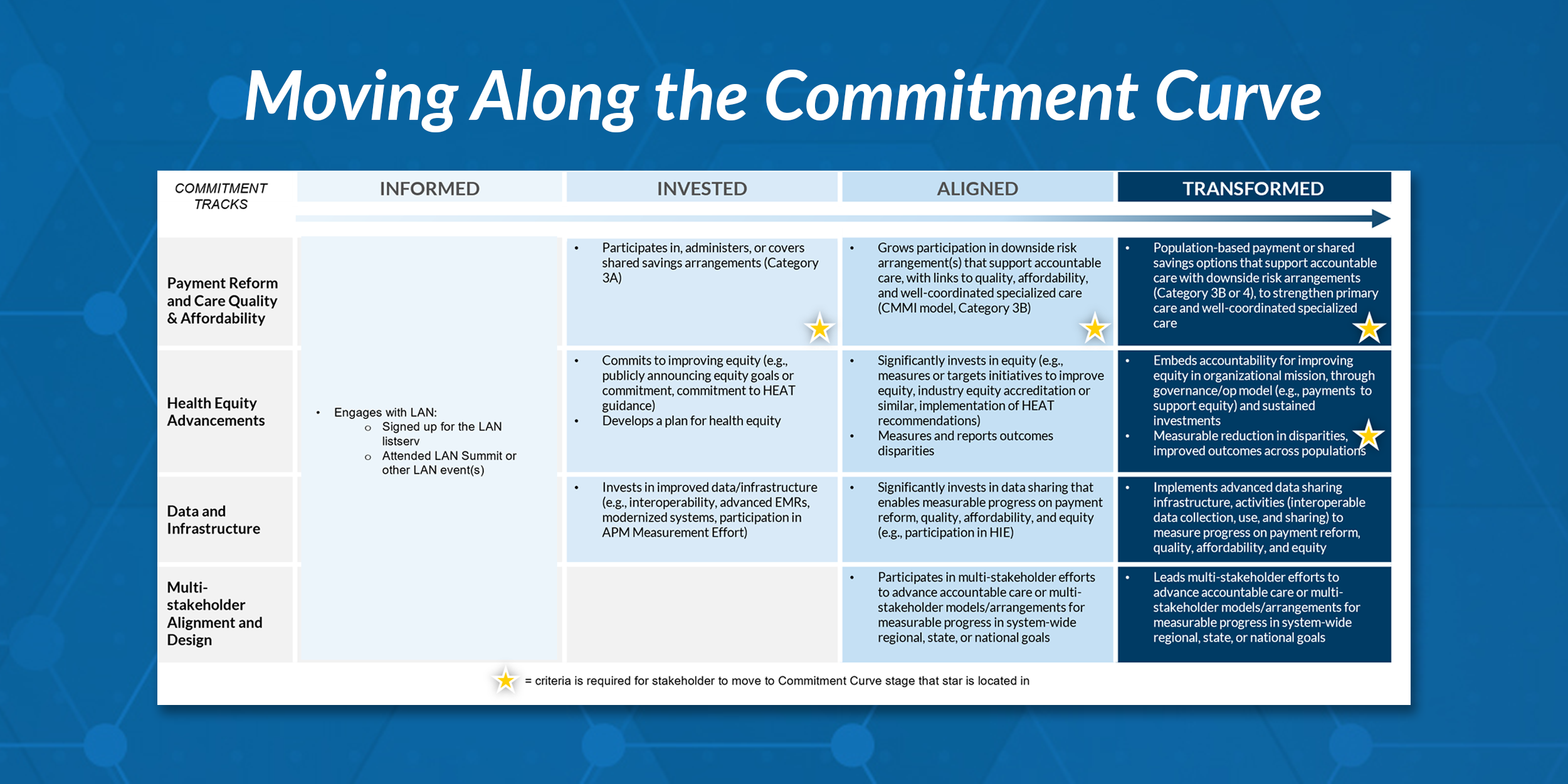

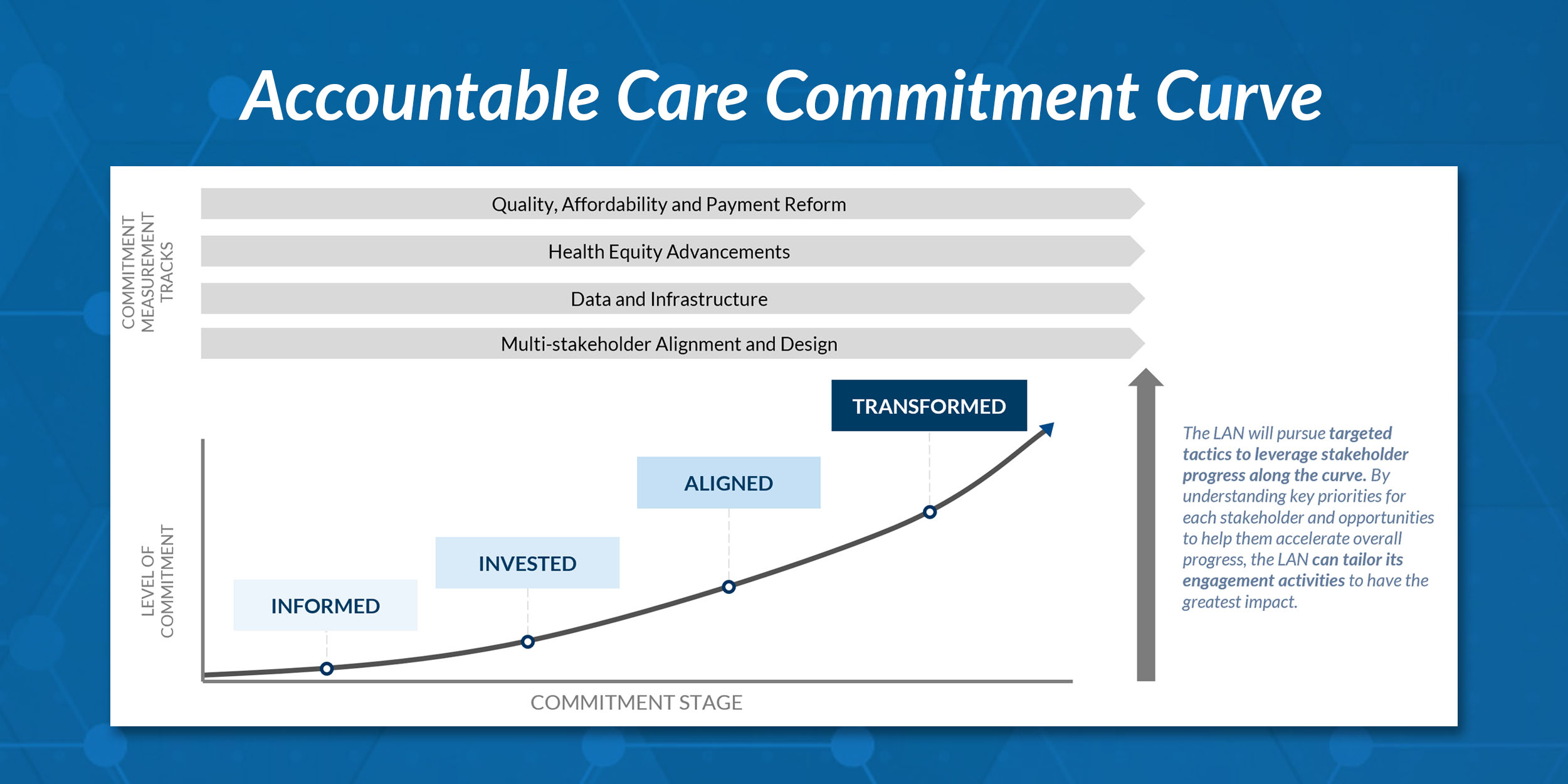

Over the past three years, advancing health equity has become a much higher priority for the LAN and CMS. And so LAN, about a year ago, created the HEAT, which is a diverse committee of equity experts from many of the different stakeholders. And the job of the HEAT is to help guide the LAN in its equity work. The guidance document you refer to, Advancing Health Equity through APMs, this provides an overall framework for thinking about equity in APMs as well as concrete, specific recommendations to help different stakeholders advance health equity through payment and care transformation.

(04:14) In your view, how do you think the healthcare landscape has changed since the HEAT was launched last year?

Even the past year there have been some changes in the healthcare landscape. And one is that first, the idea of disruptive change seems more possible than in the past. Oftentimes change is incremental, but, especially with COVID, we had changes that, had to occur because of the urgency of COVID. The two examples would be the rapid expansion of telehealth and virtual visits. And then the increased scope of practice in many states for advanced practice nursing, as an example. Changes that had been unable to occur for many years, but because of the COVID, COVID urgencies, these occurred with a lot of benefits to patients. A second change, I would say is that I think both in our country as a whole and then specifically within healthcare there is increased recognition of the importance of addressing structural racism and having an anti-racist approach as part of what we do if we really want to advance health equity.

(06:45) I want to come back and talk about that and when we talk more about APMs and their role in health equity, but just sticking on this topic of COVID since you brought that up obviously it has exposed many of the inequities in our healthcare system. So, can you talk a little bit about how the HEAT can use this data and this, moment that we are all in, to further health equity for all populations?

Advanced health equity is a matter of will, that we actually know a lot about how to advance health equity. But to be frank, advancing health equity simply has not been a high enough priority for our nation as a whole or for those of us in healthcare. this is one of those special opportunities we have where that movement towards justice, that movement towards, of equity can be faster than in the normal era. So, your specific question about data. Data are critical because if we can stratify healthcare quality and outcomes data by social risk factors, such as race, ethnicity, insurance status, rural versus urban, gender, sexual gender minorities, a variety of different factors—

If we can then stratify those quality in outcomes data, we can identify disparities. And then, based upon where those disparities are, we can do what’s so-called root cause analysis to try to understand, in our particular setting, why do these differences by gender or by race, ethnicity exist? And then the solutions we have then to address those inequities need to be geared towards addressing those root causes in your particular setting, everything is sort of the context specific that what may be affecting things here in Chicago may be different than North Carolina or Washington. So that local root cause analysis has to be done looking at the data and then the interventions designed to address your local root causes.

(9:15) You talked about how we know a lot about how to address health equity, but it hasn't been a top priority for a lot of institutions. Obviously, that's changing now, but can you talk a little bit more about some of the other challenges in terms of effect in implementing effective health equity initiatives in or through APMs?

This is one of the reasons why I think that the work of the LAN and the HEAT are so promising and exciting. Frankly, money has been a big barrier that right now there isn’t a great business case for advancing health equity. That the way the current payment systems are set up really don’t have equity as a goal. And so, a clinic or a hospital, set of providers, while they’re playing by the current rules of the game and those are the ones that they need to do to, to stay afloat financially. I think we see, a big, big change, cause the vast majority of people within healthcare, they wanna do the right thing. They wanna do well by their patients. They want to do well by their communities, no matter who a patient is, and if they are supported and given the resources and system is set in the way that it enables them to do the right thing, I think the vast majority of people and organizations will do that.

(11:05) So, given what you said about now it's a priority and making sure that there are the right payment structures to help incentivize people to address health equity. Could you talk a little bit more about the guidance document and how the HEAT is helping address some of these challenges?

The guidance document tries to both provide a big picture framework for everyone as well as starting to dive down into details of important areas. And so, on a big picture level, one might say that it’s not just payment reform for payment reform’s sake, that you don’t wanna be like a chicken with its head cutoff, just running around and trying things willy-nilly without thinking it through… it’s payment reform that needs to support and incentivize those care transformations that holistically address a patient’s medical and social needs to advance health equity. So, in some ways it’s just connecting the dot aspect. The document then concentrates upon two initial priority areas. What does care look like that would do that? So what is this good quality care? These would be things for example, that, do think about a patient holistically, do address the medical factors and the social factors that impede a patient’s best outcome. What can be done with payment to, again, incentivize advanced health equity?

One can, I think about value-based payment programs, pay-for-performance programs that, explicitly incentivized, for example, reducing a disparity and outcome between a [more] less advantaged group. A second area of payment I would think about is what I call infrastructure. One of, the wonderful things about APMs is that through different types of funding mechanisms, you do have the ability to have upfront money that can then be used to invest in what I call infrastructure, to address health equity. And these can be things like team-based care or community health workers, which typically aren’t reimbursed by many payment systems or beefing up the data systems to be able to, for example, screen for social determinants of health to be able to have the data systems that help link to appropriate partners in the community that can help with the social determinants feedback loops so that the healthcare system then knows what’s being done to address that patient’s social needs.

Those are three examples of some infrastructure. A third element of payment I would highlight is risk adjustment. This had been identified by HEAT as a key issue that wasn’t dealt with in detail in the current document, although it is the first priority topic for the HEAT’s ongoing work to start exploring risk adjustments. In fact Aparna, you’re one of the experts that the HEAT’s working with to help with this particular area. But the issue being that, on one hand, you don’t want to penalize those providers, those organizations that care for a lot of patients with high social risks. These are often patients that are, have more challenges, are harder to improve their quality of care and outcomes. So, you don’t want to penalize a provider for taking care of those patients. So, probably we need to do something like risk adjusting payment for both of a patient’s medical and social risk so that this ongoing work now. At the same time though, we don’t want to whitewash disparities. There are gonna be ways to think about payment care transformation, the flow of money, the incentives in the system, so that we can do both, of both not penalizing in fact, but rewarding people for taking care of patients that high social risk, at the same time that we don’t whitewash away inequities and that whatever we do works towards improving the equity, improving the outcomes of those at risk.

(16:01) You've explained many ways in which APMs could help advance health equity sort of reflecting back on those two key elements. Can you elaborate a little bit more in terms of APMs’ role and potentially addressing, you know, obviously the interpersonal discrimination but also any role that it might have in addressing or alleviating to some extent structural racism?

I’ll mention first two, two or three general principles. First, APMs need to be intentional about advancing health equity. Sometimes I hear people say, oh, you know just naturally as we go from fee-for-service to value-based payment or APMs, because APMs and VBP are better models, well, it’s going to fix things. Well, no, not necessarily. We can very well have inequities in VBP or APM models. So APMs have to be intentional in their design to advance health equity. Number two is I would name racism to name calling it as it is, you know, racism exists, and we need to discuss it and we need to specifically address it in our policies, our laws, the regulations, the ways we structure APMs is in some ways, it’s like the first step to having that discussion both nationally, as well as internally within the organization about issues of equity or issues of racism.

A third element is that we need to truly be patient centered, community centered and have the community and patients at the table for these discussions and in the sharing of power as we develop and implement these interventions. A lot of equity and racism has to do with understanding lived experience that, we have a very sort of divided country right now. And I think that the only way we have a chance as a country is if we basically have the sharing of stories, the sharing of experience. I think most people are good people. And then when they really hear about something in terms of a concrete person who’s in front of them, as opposed to abstract concept, it hits home. That is essentially our only hope, I think, as a country of bridging some of these divides of when people truly get to know one another and understanding each other’s lived experience, that’s the best hope we have.

And so, what this means for like an APM or health organization is that that’s the point about bringing patients and communities in as we are thinking about the problem of advancing equity and the solutions, is to understand the lived experience, what the community thinks are gonna be the most likely solutions that will be effective. I mean, who knows the problem the best? Well, the community they live the experienced and whatnot. And so, those are critical elements of the solution. The point too, you raised this, one more riff here, the point about implicit bias, it gets back into discussions that the best training that I have had in terms of when I’ve been a trainee in this is when is the opportunity to have the sharing of the lived experience.

So, the sharing of your colleagues’ experience in their lives, there’s things that you just have no idea about probably in terms of your colleagues until you have like these honest discussions that to me has been, where I have found the most, well, my own experience as well. And I think about the people that I work with or the wider University of Chicago, it was when there are these opportunities to have these transformative shared lived experience discussions. They are hard, they are challenging, these are not easy discussions, they’re tough issues. But they’re the ones that tend to have the most impact in terms of actually changing our behavior in our organizations.

(20:19) So, since you mentioned the University of Chicago and some of your experience there, obviously you’re a practicing physician and given your work also leading the RWJF grant that you mentioned earlier, are there particular examples that you can sort of describe in further detail in terms of how the use of multifactorial or multi-component interventions have been used to advance health equity using APMs and payment, but also some of these other approaches that you mentioned?

I’ll give you two or three examples. So, one is for another program I co-direct, this Merck Foundation program called bridging the gap program of working with eight different urban and rural communities to improve diabetes population outcomes. And one of our most successful teams is west, UPMC Western Maryland. This is a system, health system that’s located in the far western part of Maryland. This is the panhandle part of Maryland, which is rural part of Appalachia. And as many of the listeners know the state of Maryland has an all-payer system where the health organizations are incentivized based upon their total cost of care. So UPMC Western Maryland, they have systems very similar to APMs where you have these total cost incentives mixed within quality-of-care metrics, incentives.

What they have found is that because of the financial incentives and the way that there’s flexible payment, they’ve invested in creating a center for clinical resources where this is a team that anyone can refer their patient, this team, which will do a holistic addressing of medical and social needs. And so they will do, for example, detailed social needs screening, they will do the partnerships with the community organizations that can help with the social needs. And they have found, like in this particular example this center has been able to, for their diabetes patients improve their sugar control as measured by A1C, as well as decrease all cause hospitalizations in this patient population. That’s one example. Second example I’ll give is that oftentimes some of the most exciting work is done at the state level where there’s, in the states you have fifty different states for experiments in terms of the Medicaid program.

So, the states of Oregon and Minnesota are two of the states that are most advanced regarding the way they have structured APMs and their different models for advancing health equity. So, Oregon, they have something called CCOs, which are essentially ACOs, and they basically incentivize equity. They have a flexible payment mechanisms to be able to more flexibly use money to address the medical and social needs. Minnesota, they explicitly call out racism and their managed care contracts are looking at ways to reward those managed organizations that are doing serious efforts to address racism, address equity. Third example I give is, again, from our bridge in the gap program. This is a federally qualified health center in Washington, DC named La Clinica that works with mostly immigrants, El Salvador population that have a complicated set of medical and social needs.

(24:39) Obviously, room for improvement with the one in DC in terms of giving them more payment support, I guess, but from your perspective and based on your experience, how do you think we can replicate this kind of success nationwide for us? I think to tackle health equity and reduce disparities would require scaling and more broad scale adoption of these kinds of models. So, can you talk a little bit about what, what would need to happen?

It does come back to what we talked a little bit earlier, that first it’s will that you could have wonderful ideas and plans regarding your payment and your care transformation and all, but frankly, if there’s not a will both within your individual organization as well as at the state and national level to create basically the payment regulations and all that support, all this, well, you know, ain’t gonna go very far. So, the will is incredibly important. You know, the point about it all has to be contextualized to your local context.

So, in one hand, there isn’t really sort of like, oh, just take these off-the-shelf solutions and plug and play. There were all these good models, but ultimately, you have to do the thing of looking at your own data, doing the root cause analysis in conjunction with your patients and partners to identify, in your particular setting, what are the specific drivers of the disparities, and then the solutions, again, need to be addressed – what is your local issues? That’s a generic approach, but again, when it comes down to it, the things that work are fairly generic. So, things, these are things, for example, like team-based care, you know, things that involve close personal relationships with patients, close following and monitor and patients. So that’s why team-based care oftentimes works, that you have a team that, you know, can do all the handoffs.

So, someone will see them in the clinic. Someone will do the telephone calls to home, and someone will do home visits so all that’s involved, culturally tailored approaches better than generic one-size-fits-all approaches, not surprisingly, involving the patients in the communities and the solutions, multifactorial approaches from also all of the inequities. It’s not just one thing that causes it. There may be a whole host of things, but maybe there’s three or four really important ones that you start with. Those are some examples of some of the general principles that apply, but again, it has to be tailored to one’s own particular situation and all. So that’s why, in some ways, it’s a process, not just take this solution out the shelf and plug it in.

(27:27) Earlier you talked about how COVID, forced us to make some changes very rapidly, right? You talked about disruptive change in terms of telehealth and scope of practice laws and so forth. What do you think are some of the lessons learned from the experience with this pandemic that you would like to see incorporated into APM design?

I point out maybe four lessons we learned from the pandemic. So one is that, that we need to be intentional about designing our solutions to advance health equity. So, I think we found, for example, like the rollout of the COVID vaccine where equity, frankly, was not prioritized highly enough. We had the national guidelines that, that didn’t lead to adequate allocation of, of vaccines or systems or processes to get vaccines equitably in the community. So, the point being that we need to intentionally design APMs to advance health equity. It goes along line with the APMs vision regarding its role in population health, the ethics of, of serving the community and the social justice imperative we’ve seen with, with COVID. And in general, with healthcare, a second lesson from the pandemic is that we need to address social determinants of health.

Oftentimes the medical parts of the problem are the easier problems to face, as opposed to some of the social determinants of health we found, like for COVID and the need to think about patients holistically in terms of their medical issues through economic use the health beliefs, if we’re going to, in this case, for example, get communities vaccinated. A third is behavioral. And so that and any of the clinicians here know that behavioral issues are such a heavy component of many of the patients we see there’s this famous quote from Francis Collins, the most recent NIH director, which some people may not heard of yet, where he said that he was asked, “well, now that you’ve finished your term as NIH director, is there anything you wish you would’ve done differently?”

And one of the first things he said was that I really wish I had put more money into the behavioral science research, and I think it was coming from his perspective and having to deal with COVID and seeing all this vaccine, he’s seen it all. And again, like any clinician will say, well, yeah, coming to the club a little bit late, but great that he came to that recognition that again, what any clinician and a person sees right off the bat, behavioral issues, just such an important part of overall health. The last thing I’ll mention again is we learned from the pandemic that racism is a big issue. And so, we need to have an explicit anti-racism lens as we think about some of the equity Issues within APMs and nationally.

(30:35) I want to pick up on something you said, which is the importance of addressing social risk factors and showing transportation, housing access to nutritious food and so forth. As a practicing clinician what has been your experience incorporating those factors, into care, whether you as a practicing clinician or within the University of Chicago health system, what are some things that have worked and what are some of the ongoing challenges?

When you hear this term, social determinants of health, I would think about it on two levels. One is the individual level. In other words I was in clinic yesterday. And I’m seeing my nine morning patients which patients have particular social needs that are issues that we need to address. So, it’s the individual level, individual patient. The second level is more the systems and the structure. There are social determinants of health in the community that are driving health inequities. Things like, you know, poverty or poor housing or inadequate education or criminal injustice and whatnot. And so, as a clinician, I think there’s a, a role for us on the two levels. So clearly for example, like at the University of Chicago, we now have within our EMR, there’s the social needs screening tool that is used.

We also have now, we are working with Now Pow, this is one of the half dozen of these different companies that help then take social needs screening data, and then determine in the patient’s neighborhoods, what are the relevant social service agencies or resources that would help address that, that housing issue or that food insecurity issue. And then there’re the feedback loops of then, that agency then feeding back information back to the healthcare system. So, we know what’s happening in terms of that their holistic care, and all at the same time some of this is where it’s not, it shouldn’t just be the clinician that does this. Here’s where, then the clinic, the overall hospital, the overall integrated delivery system needs to do their part in terms of creating, help creating that system that data system or help creating that team that can do that bridge the community and whatnot, or that health system can work in terms of then like in this negotiations then with like the payers or the state regarding the creating the funding streams for this necessary work.

It shouldn’t just be the clinician. And that’s what burns clinicians out, at least the frustration. I think there are plenty of things that we can do all different levels, whether individual, organizational, policy level to create that, that integrated system care that can look at people as individuals and communities as the systems, and then address them, both the individual and systemic, structural social determinants of health.

(33:36) How different do you think care will be in the next one to five years, if you were to look at your crystal ball?

I’ll point out three different trends, which I think are already happening and I think will accelerate. One is this move from still a predominantly medically oriented healthcare system. The one that thinks about patients truly in a more holistic way as people that have medical and social issues and as individuals who also live within communities. So, APMs, I think be part of that, that trend also. Second general trend is a shift from a predominantly inpatient-based healthcare system to one that increasingly shifts care to the home in virtual settings. We saw with telehealth of the value that telehealth and we need to do more about shifting things out of the hospital. We can probably be more efficient in terms of the mix of what can be, needs to be done.

So, that’s an exciting shift. A third shift I would say is that we’re gonna see over time, just increasing amounts of real-time health data and social data available. And now, then, with advances in machine learning, artificial intelligence, we should have faster ways to process, analyze, and then respond to these real-time data with systems. We need to create, to be able to handle this data and then, to then respond in terms of how it interacts them with the patients. It’s all very, very exciting. The trends. I would say though, that all these have potential advanced health equity, health equity, if we address them appropriately, but all these three trends also could exacerbate inequities if we don’t basically be intentional about designing our systems to address equity issues.

(35:42) Is there anything else that we didn't cover that you would like to take a few minutes to address?

I’d just like to harken back to what we talked about at the beginning, Aparna, of how this is really, really a special time in our country. We, we got a lot of challenges and there’s a lot of threats to our country in our democracy. But at the same time, there is one of these opportunities for transformative change. I believe in our healthcare sector generally, and specifically for advancing health equity, this will require are both local leadership. So, I know that many of our listeners are leaders in your own organizations. So, it will require local leadership. And it’s much easier for us as local leaders if this wind behind our sails at the state or national level. So, for example, national efforts like the LAN or some of the CMS’s new efforts regarding equity or the work of the HEAT all have tremendous potential because they can be so synergistic and to support the local leadership with what they wanna do anyway, in terms of providing the best quality care to advance health equity.

So, there is a tremendous opportunity for the LAN and CMS here. And so, I urge everyone to work both locally as well as nationally, such as through the LAN, to advance and synergize our efforts, earning health equity. I am optimistic about our chances of significantly advancing equity over the next few years. I, I’m sort of on, one more like glass half full, as opposed to glass half empty people, empty, empty people that some people talk about how policy and, and healthcare transformation, some of it’s just serendipity. And when there are these windows of opportunity, we got one right now.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models. Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices.

Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices. Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System.

Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System. Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities.

Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities. Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.