Online Resource Bank

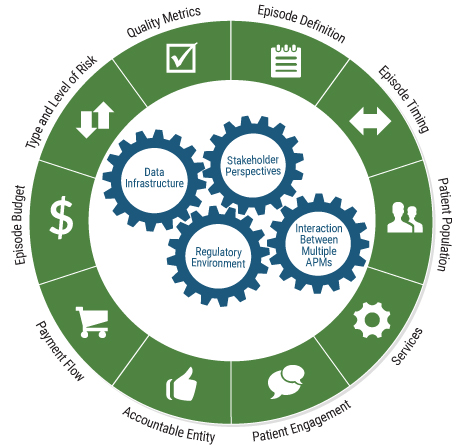

Episode Definition

The episode is defined to include the large majority of births, including the newborn care, that are lower-risk. While not necessarily lower risk, episode payment may also be considered appropriate for women who may be at elevated risk due to conditions that have defined and predictable care trajectories, such as gestational diabetes. As the CEP model matures, some groups with significant high-risk pregnancy experience and capacity may seek to manage the entire continuum of risk.

Setting the Patient Population E-book | Setting the Patient Population Resource Slides | Setting the Patient Population Meeting Summary

When does the episode start and how long does it last?

By definition, a perinatal care patient has a specific start and end point to their maternity condition. However, there are different ways in which a maternity episode can be defined. Decisions must be made regarding when the episode starts and ends, in order to determine services and budget.

- Options for the starting point include 1) when a payer is notified via claims of a prenatal care visit, or 2) when a live birth is identified through retrospective review of claims

- Options for determining the episode length can include

- Using a “look back” period. The look back could be 270 days prior to delivery, or the first visit at which a pregnancy is confirmed.

- Using a “look forward” methodology, e.g. 60 days post-partum for the mother/30 days postpartum for the baby, based on the date of live birth.

Are there specific patients for whom a provider will or will not receive reimbursement through the episode model?

Payers and providers need to know which patients are being cared for under and episode payment model; thus decisions must be made about whether the model will cover all patients, or whether certain patients will continue to be paid through a Fee-for-Service reimbursement, and what criteria determines this categorization. Options include:

- Include all patients

- Establish exclusions:

- High-risk pregnancies (which can be defined in many ways and negotiable, and identified after-the-fact for retrospective episodes).

- Women who did not receive care from delivering provider during the prenatal time period.

- Women whose pregnancy was not confirmed until a pre-negotiated week of pregnancy (this includes women who did not seek services at the start of their pregnancy).

What services are included in the episode budget?

The goal of an episode payment model is to deliver all necessary services to the patient with the goal of achieving a successful outcome at an appropriate cost (i.e within the episode budget). Questions to be considered include:

- Will the episode budget be set to reasonably include all services inclusive of pregnancy, or will the budget reflect a subset of services?

- If the episode population includes the baby, will the services include all NICU costs?

Episode Timing

The episode should begin 40 weeks before the birth and end 60 days postpartum for the woman, and 30 days post-birth for the baby.

When does the episode start and how long does it last?

By definition, a perinatal care patient has a specific start and end point to their maternity condition. However, there are different ways in which a maternity episode can be defined. Decisions must be made regarding when the episode starts and ends, in order to determine services and budget.

- Options for the starting point include 1) when a payer is notified via claims of a prenatal care visit, or 2) when a live birth is identified through retrospective review of claims

- Options for determining the episode length can include

- Using a “look back” period. The look back could be 270 days prior to delivery, or the first visit at which a pregnancy is confirmed.

- Using a “look forward” methodology, e.g. 60 days post-partum for the mother/30 days postpartum for the baby, based on the date of live birth.

Patient Population

The episode should primarily include the large majority of births, including newborn care, that are lower-risk. The Work Group also supports CEP for women who may be at elevated risk because of predictable risk factors that have defined care trajectories, such as gestational diabetes.

Setting the Patient Population E-book | Setting the Patient Population Resource Slides | Setting the Patient Population Meeting Summary

Are there specific patients for whom a provider will or will not receive reimbursement through the episode model?

Payers and providers need to know which patients are being cared for under and episode payment model; thus decisions must be made about whether the model will cover all patients, or whether certain patients will continue to be paid through a Fee-for-Service reimbursement, and what criteria determines this categorization. Options include:

- Include all patients

- Establish exclusions:

- High-risk pregnancies (which can be defined in many ways and negotiable, and identified after-the-fact for retrospective episodes).

- Women who did not receive care from delivering provider during the prenatal time period.

- Women whose pregnancy was not confirmed until a pre-negotiated week of pregnancy (this includes women who did not seek services at the start of their pregnancy).

Services

Covered services include all services provided during pregnancy, labor and birth, and the postpartum period (for the women) and newborn care for the baby. Exclusions should be limited. Initiatives should also consider including high-value support services, such as doula care and prenatal and parenting education.

Alternative Models of Maternity Care Delivery & Determining Services E-book | Alternative Models of Maternity Care Delivery & Determining Services Resource Slides | Alternative Models of Maternity Care and Delivery Meeting Summary

What services are included in the episode budget?

The goal of an episode payment model is to deliver all necessary services to the patient with the goal of achieving a successful outcome at an appropriate cost (i.e within the episode budget). Questions to be considered include:

- Will the episode budget be set to reasonably include all services inclusive of pregnancy, or will the budget reflect a subset of services?

- If the episode population includes the baby, will the services include all NICU costs?

Patient Engagement

Engaging women and their families is critical in all three phases of the episode—prenatal, labor and birth, and postpartum/newborn—to contribute to the foundation for healthy women and babies.

Engaging the patient across the full episode of maternity care provides important opportunities to contribute to maternity care episode payment success. The maternity care episode should support the standardized use of patient engagement strategies and models, particularly given that these strategies are typically underutilized.

- Shared Care Planning: After a maternity care provider is selected, shared care planning should be integrated throughout the episode, including goal setting, shared decision-making, and documenting preferences and decisions, with the understanding that circumstances can change over time. Optimally, information technology makes the care plan available across the episode at all sites of care and to all members of the care team, including women and families.

- Enhanced Services: Some patient engagement efforts involve enhanced services, such as maternity home and group prenatal visits. Others include high-quality childbirth education classes to engage women in learning about options and making informed decisions about their care. Benefit policies vary, but many Medicaid programs include childbirth education as a covered benefit. Healthy People 2020 includes a goal to increase the number of women who attend childbirth classes (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2016). These classes can decrease a woman’s fears about labor and birth and are shown to be a critical factor in reducing early elective births.

- Shared Decision-Making: Other examples of tools for patient engagement include shared decision-making aids, such as the decision aids developed by the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation and Childbirth Connection (now available through Healthwise) and the use of mobile devices, including Text4baby, to access health information and services that provide individualized information based on the pregnancy stage and individual needs.

Episode Budget

The episode price should strike a balance between provider-specific and multi-provider/regional utilization history. The price should: 1) acknowledge achievable efficiencies already gained by previous initiatives; 2) reflect a level that potential provider participants see as feasible to attain; and 3) include the cost of services that help achieve the goals of episode payment.

Episode Budget and Price E-book | Episode Budget and Price Resource Slides | Setting the Episode Budget Meeting Summary

Contracting with Providers E-book | Contracting with Providers Resource Slides | Contracting with Providers Meeting Summary

Determining the data that are to be used: Payers can either use:

- Historical data (the historical “look back” period may be anywhere from one-to-three years) for individual physicians, provider groups, ACOS/IPAs, or across a geographic area or marketplace

- Calculate the budget based on expected use of services, using payer’s current reimbursement rates.

Adjusting the budget for risk factors: Payers need to determine if an episode will be risk-adjusted or if there will only be the “flat rate” budget. If there is to be risk adjustment, the following questions must be answered:

- Will the payer offer a margin for providers (might be considered when provider efficiency is high)?

- Will the payer implement an underuse fee, whereby if certain services aren’t offered they will be automatically added to the price (budget) to prevent underuse of care?

- Will the payer offer stop-loss protection for outlier cases?

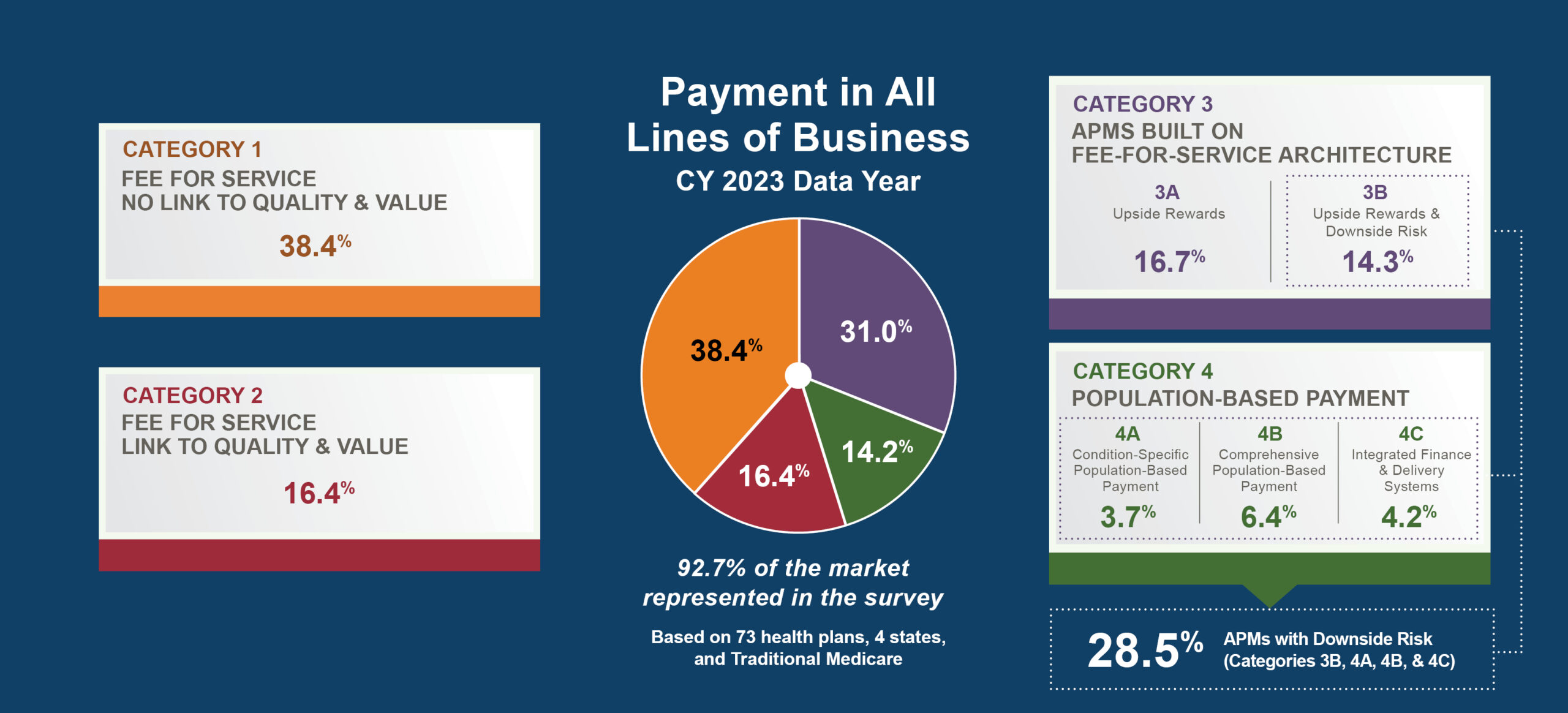

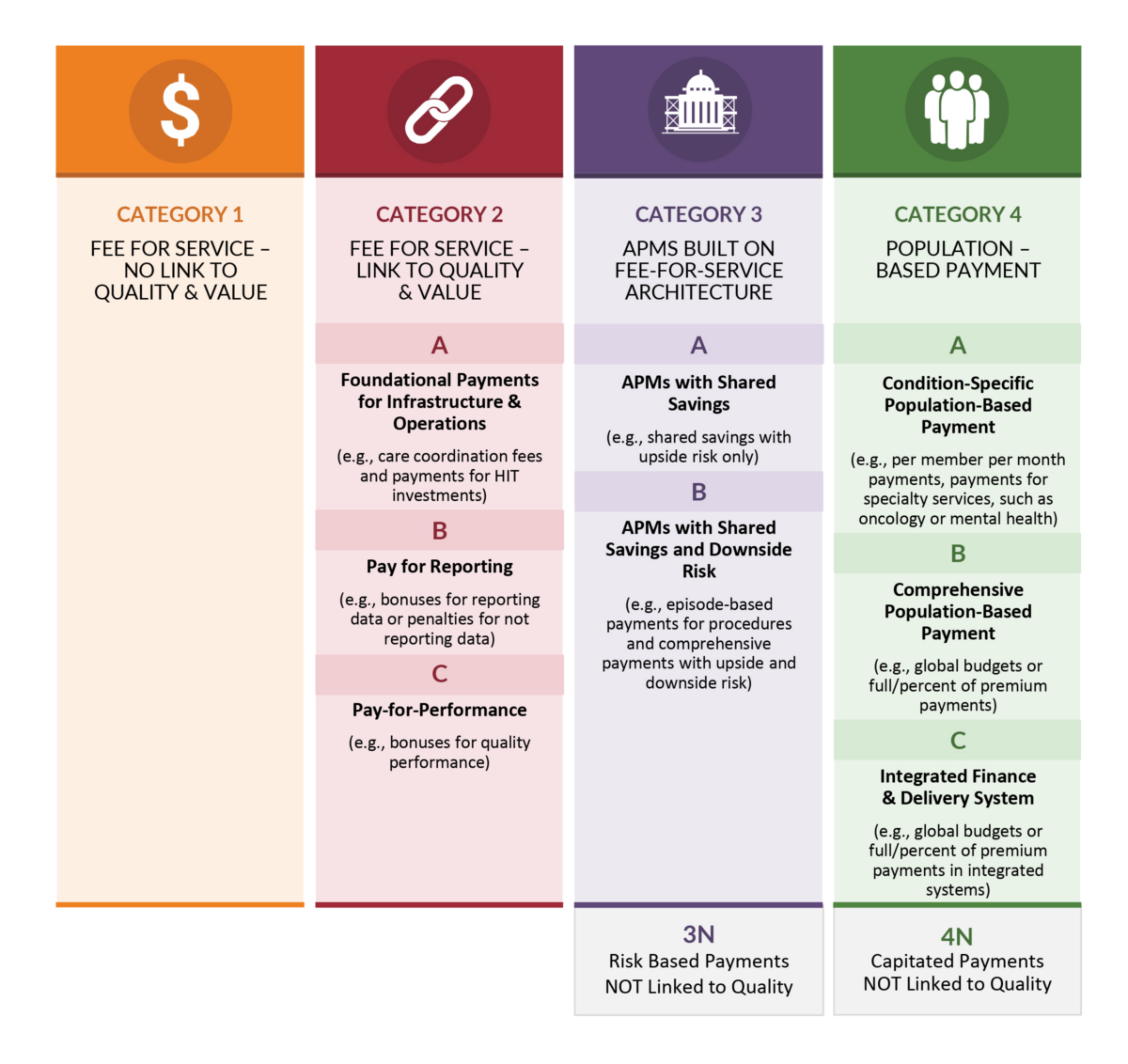

Designing the savings/risk model: As an APM Framework Category 3 model, episodes may incorporate shared savings and/or shared risk. Payers need to determine the following:

- Will the payer share any savings the provider generates? If so, what percentage?ill the payer expect the provider to share in any losses that are incurred? If so, what percentage?

- Will the provider be fully responsible for all losses and able to keep all savings it generates?/li>

- Will the payer automatically take a percentage of the budget as its built in savings?

Type and Level of Risk

The goal should be to utilize both upside reward and downside risk. Transition periods and risk mitigation strategies should be used to encourage broad provider participation and support inclusion of as broad a patient population as possible.

Episode Budget and Price E-book | Episode Budget and Price Resource Slides | Setting the Episode Budget Meeting Summary

Contracting with Providers E-book | Contracting with Providers Resource Slides | Contracting with Providers Meeting Summary

Adjusting the budget for risk factors: Payers need to determine if an episode will be risk-adjusted or if there will only be the “flat rate” budget. If there is to be risk adjustment, the following questions must be answered:

- Will the payer offer a margin for providers (might be considered when provider efficiency is high)?

- Will the payer implement an underuse fee, whereby if certain services aren’t offered they will be automatically added to the price (budget) to prevent underuse of care?

- Will the payer offer stop-loss protection for outlier cases?

Designing the savings/risk model: As an APM Framework Category 3 model, episodes may incorporate shared savings and/or shared risk. Payers need to determine the following:

- Will the payer share any savings the provider generates? If so, what percentage?

- Will the payer expect the provider to share in any losses that are incurred? If so, what percentage?

- Will the provider be fully responsible for all losses and able to keep all savings it generates?/li>

- Will the payer automatically take a percentage of the budget as its built in savings?

Quality Metrics

Prioritize use of metrics that capture the goals of the episode, including outcome metrics, particularly patient-reported outcome and functional status measures; use quality scorecards to track performance on quality and inform decisions related to payment; and use quality information and other supports to communicate with, and engage patients and other stakeholders.

Contracting with Providers E-book | Contracting with Providers Resource Slides | Contracting with Providers Meeting Summary

Quality Measures Part 1 E-book | Quality Measures Part 1 Resource Slides | Quality Measures Part 1 Meeting Summary

Quality Measures Part 2 E-book | Quality Measures Part 2 Resource Slides | Quality Measures Part 2 Meeting Summary

Which measures will be utilized to measure quality?

The process of selecting the measures that most closely relate to the goals of the episode model should include examining the following questions:

- What are the areas for improvement based on current performance?

- How can the designing entity best engage providers and stakeholders in choosing measures?

- What measures are already being collected, reported or publicly available, including those used by other payers, and can feasibly be integrated into this model with little burden or infrastructure cost?

- Which measures have meaningful state, regional or national benchmarks and can serve multiple purposes through implementation in this model?

How will the payer and provider determine performance? If payment or participation in general in the model will be linked to quality performance, the designing entity must determine how performance will be assessed.

Options include:

- Assess performance relative to benchmarks or targets

- Assess performance relative to other providers

- Assess performance relative to individual provider’s past performance

How will performance on measures be tied to savings or risk? There are various ways to link payment to performance, once the performance assessment is made. Two options include:

- Integrate quality directly into the financial model and allow for performance to adjust the savings (or loss) percentages.

- Use quality performance independently of the financial model, and reward with a separate quality bonus pool or another mechanism.

Further, to consistently improve upon patient engagement activities, it will be important to use patient activation metrics to track overall patient engagement. A change score for the Patient Activation Measure (a healthy person version recently endorsed by the National Quality Forum [NQF]) administered near the beginning and end of pregnancy would incentivize those participating in the episode payment to build women’s skills, knowledge, and confidence as they approach giving birth and new parenthood.

Payment Flow

The unique circumstances of the episode initiative will determine the payment flow. The two primary options are: 1) a prospectively established price that is paid as one payment to the accountable entity; or 2) upfront FFS payment to individual providers within the episode with retrospective reconciliation and a potential for shared savings/losses.

Contracting with Providers E-book | Contracting with Providers Resource Slides | Contracting with Providers Meeting Summary

State Payers and MCOs Meeting Summary

How will payment be operationalized?

- Fee-for-service with retrospective reconciliation to the episode budget.

- Prospectively paid at the start of the episode. (Note: this requires the episode to be triggered by a prenatal care visit, not a live birth)

When will reconciliation payments be made?

- With what frequency will the payer reconcile payments?

- Will the provider face penalties for claims not submitted in a timely manner?

- Will the payer face penalties for late reconciliation?

How will the payer distribute payments to the contracting entity?

- Depending on the contracting method, the payer needs to identify how payments will be distributed.

- Will accountable providers have any requirements to distribute shared savings payments to subcontractors (if applicable?)

Accountable Entity

The accountable entity should be chosen based on readiness to re-engineer change in the way care is delivered to the patient and to accept risk. In this model, the accountable entity will likely require a degree of shared accountability, given the number of clinicians working to care for a patient.

Contracting with Providers E-book | Contracting with Providers Resource Slides | Contracting with Providers Meeting Summary

Quality Measures Part 1 E-book | Quality Measures Part 1 Resource Slides | Quality Measures Part 1 Meeting Summary

Quality Measures Part 2 E-book | Quality Measures Part 2 Resource Slides | Quality Measures Part 2 Meeting Summary

Central to the determination of what provider entity or entities should be accountable for the episode is the question of provider readiness to both re-engineer the care delivery model for the patient, and in the process, accept the financial risk they might incur.

- Payers should work with the accountable entity to assess their readiness, and promote collaboration to allow for multiple providers within a maternity care team to share the risk and reward in such a manner that all are engaged in creating a seamless, efficient, patient-centered care process. This process can require active participation across the continuum by aligning incentives across contracts in the private sector, because the payer often has contracts directly with providers. Optimally, accountability would be shared among all involved providers, if incentives are aligned.

- Another challenge related to assigning the accountable entity relates to situations in which the newborn needs intensive care. In such an instance, the newborn specialist will take over as the care manager. While we anticipate that limiting the population to lower-risk pregnancies, stop/loss limits and risk adjustment may limit the risk of the assigned accountable entity. It will be important for the team that managed the birth to incorporate the newborn specialist into the process.

Factors to Weight in Determining Readiness for Episode Accountability

- Minimum volume standards,

- Ability to deliver, or contract for, the entire bundle of services to be rendered;

- Demonstrated ability to care for total joint replacement patients;

- Effective discharge planning capacities, including systems to include rehabilitation physicians and extenders early in the discharge planning process to help in identifying the proper trajectory of patients and their care;

- Ability to manage transitions or handoffs from one setting to another when necessary (e.g. entry, transitions, and discharge); and

- Ability to track quality indicators and patient outcomes across an array of services and settings

- Demonstrated dedication of the hospital, physicians, nurses, therapists, and other clinical professionals’ time to the programs;

- Capacity to monitor patient clinical status and coordinate medical management and reconciliation as patients progress across acute and post-acute care settings;

- Ability to coordinate with other community services to foster the patient’s independence;

- Necessary financial systems to administer payment across multiple entities; and

- Ability to tolerate financial risk, including post-discharge outcomes, such as readmissions, and understand its own risk exposure.

Stakeholder Perspectives

Ensure that the voices of all stakeholders— consumers, patients, providers, payers, states, and purchasers—are included in the design and operation of episode payments.

Making the Business Case for Maternity APMs Infographic | Making the Business Case for Maternity APMs Issue Brief

Contracting with Providers E-book | Contracting with Providers Resource Slides | Contracting with Providers Meeting Summary

Data Infrastructure E-book | Data Infrastructure Resource Slides | Data Infrastructure Meeting Summary

It is important to understand the varied perspectives of those who will be impacted by the clinical episode payment. Each stakeholder, whether payer, provider, consumer, or purchaser, has unique expectations, goals, and limitations during the design of an episode payment. Because of the multiplicity of these diverse perspectives, it is important to consider all stakeholder voices in the design and operation of episode payments.

- Patients and Consumers: Patients and their families, caregivers, and consumers contribute to, and benefit from, episode payment models, including by participating in design, governance, evaluation, and improvement of episode payment models. They can use high-quality decision tools to decide about appropriate care. When patients and caregivers have access to meaningful quality and cost information, they are able to make thoughtful care arrangements that favor the highest value care and providers.

- Payers: Commercial health plans and Medicaid seek to create incentives for providers to coordinate care across provider types and thus, create efficiencies that decrease costs for a bundle of services. They are often willing to invest in strong data infrastructure for episode payment implementation, as well as develop new contracting procedures with participating providers.

- Providers: Providers (clinicians and facilities) look for indicators of sufficient leadership and accountability for episode payment to be established to ensure that the goals of care re-design and care coordination across settings and providers are prioritized over cost savings. They are interested in aligning financial incentives, data requirements, and quality measurement requirements across all payers with which they contract.

- Employers and Purchasers: Purchasers can advance the goal of aligning incentives between themselves and providers through episode payment. Purchasers may also be interested in integrating tiered networks within a bundled payment model to provide incentives to employees to seek care from high-performing providers and in improving value through enhanced benefits. Large purchasers hold significant leverage with payers and providers and can push for episode payment within their contracting negotiations. In the case of maternity care, this leverage is held by employers and state Medicaid agencies that can encourage their managed care organizations (MCOs) to use bundled payment for maternity care.

Data Infrastructure

Understand and develop the systems that are needed to successfully operationalize episode payments.

Data Infrastructure E-book | Data Infrastructure Resource Slides | Data Infrastructure Meeting Summary

How will data be used to assist providers in managing to an episode budget?

- What data should providers expect to get from payers to help them track costs relative to budget for each episode?

- How will the data be shared, (e.g., web portal) and with what frequency (e.g., monthly, near-real-time)?

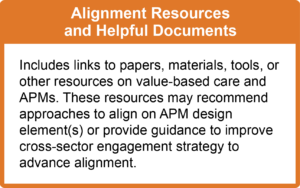

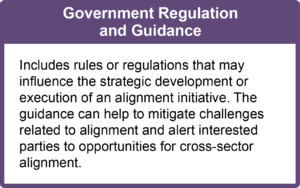

Regulatory Environment

Understand relevant state and/or federal regulations and how they may impact the design and implementation of episode models.

Pursuing an episode payment initiative requires remaining cognizant of the statutory and regulatory framework that may impact the manner in which it creates relationships with providers and the way incentive and risk structures are established. Three federal laws of significant importance to health care systems are the physician self-referral law, the anti-kickback statute, and the civil monetary penalty (CMP) laws. There are also regulatory areas that may impact maternity payment strategy in particular.

- States define the types of providers, including practitioners, and settings of care that support birth. They define licensure and certification of providers and the scope of practice under which the providers operate. At a minimum, these regulations will impact decisions related to participating providers, services covered, and episode price determination. For example, laws that require written agreements for transfers between birth centers and hospitals or that require OB/GYN supervision of births in a birth center can limit the availability of that birthing option if no hospital or OB/GYN is willing to engage in such an agreement. Other state laws create a more restrictive minimum length of stay for a birth than the federal minimum and may also need to be considered.

- The Medicaid context is important to consider, given a large number of births are paid for by Medicaid. A high percentage of those births are paid through MCOs; therefore, it will be important to consider the manner in which a state contracts with MCOs. These contracts must determine whether states could encourage such payment arrangements or whether the Medicaid MCOs may be interested in paying for maternity care in that manner without state encouragement. There are examples whereby a state encourages these types of payment arrangements through their contracted MCOs; whereas, other states have MCOs build bundled payments for maternity care into their contracts with providers without state encouragement. We note that, given limits on re-assignment of claims, if a state pays FFS for births under Medicaid it may not be feasible to prospectively pay for a clinical episode of care to one accountable entity that would then remunerate other providers.

It will be important for provider organizations to discuss with legal counsel the potential implications of these and other laws on proposed arrangements for clinical episode payment.

Interaction Between Multiple APMs

Consider the context of the broader strategic goals when deciding whether to implement multiple payment models and address the operational issues that arise when two entities may have responsibility for the costs of care for one patient.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models. Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices.

Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices. Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System.

Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System. Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities.

Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities. Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.