Why Regional Data and Local Relationships Will Reform Health Care Payment Nationally

- February 8, 2016

- Posted by: Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network

- Category: Blog

The United States health care system is on an unsustainable course. Our $3.1 trillion in annual health care spending represents more than 17% of the nation’s GDP and is projected to increase 7% to 10% annually in the years ahead. Studies show that rising health care costs have consumed 10 years of U.S. wage growth.

As personal incomes have lagged, essential and discretionary spending has declined and businesses have been forced to divert resources away from reinvestment, limiting prospects for innovation and growth. And as health care costs grow, government expenditures that could bolster education, infrastructure, research and development, and the arts decline. Left unchecked, rising health care costs have the potential to undermine communities and bankrupt the U.S. economy.

In response to the unending rise in health care costs, the country is engineering a dramatic transition to value-based payment. In the private sector, this is driven by employers seeking higher quality care for lower cost on behalf of their employees. Health plans are also designing new payment models that support better value. Congress passed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) that mandates a reallocation of how providers are paid based on value, quality, patient experience, and efficient use of resources. This momentum from both the public and private sectors is beginning to drive tremendous change.

Using Data to Define Quality Improvements

But you can’t pay for value if you can’t define it. All of the emerging policy and market changes depend on transparent, standardized information that accurately describes the cost and quality of medical care. But that information is simply not available consistently. Payers currently require multiple different metrics that rarely align and may not reflect provider or patient priorities.

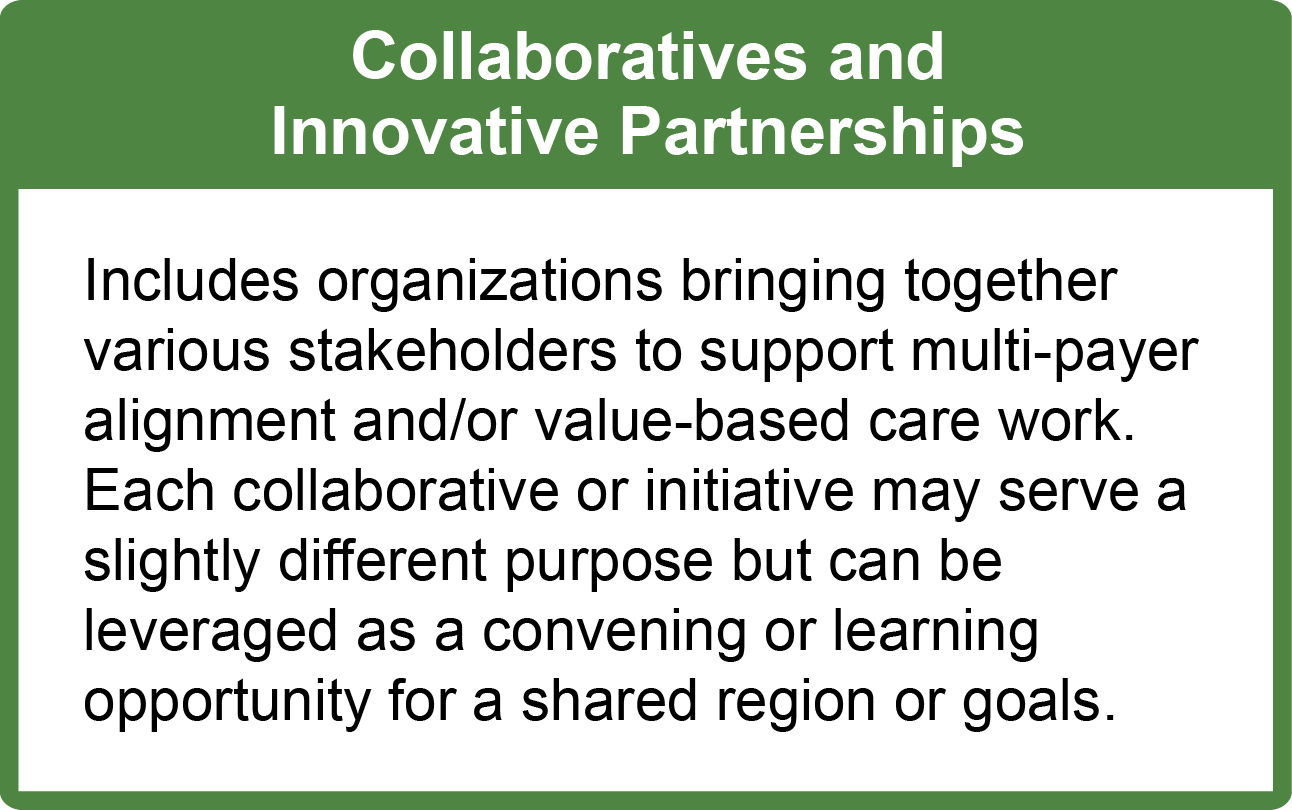

Emerging payment models are oriented towards payments for populations. Those new models will not only require alignment across payers but also require new metrics, new data systems, and new approaches to transparency. One example of how data improves care and reduces costs is the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative pilot in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a multi-payer initiative convened by MyHealth Access Network, one of NRHI’s member regional health improvement collaboratives.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma, Community Care of Oklahoma, and the Oklahoma HealthCare Authority (Oklahoma Medicaid) worked with a network of 68 primary care practices that together care for 200,000 patients. Clinical data from electronic health records and claims information were used to risk-stratify patients, identify gaps in care, and bring employers, insurers, and providers to work together to review the quality and cost of care. All of the practices shared their cost and performance data, which created a culture of collaboration and a focus on outcomes.

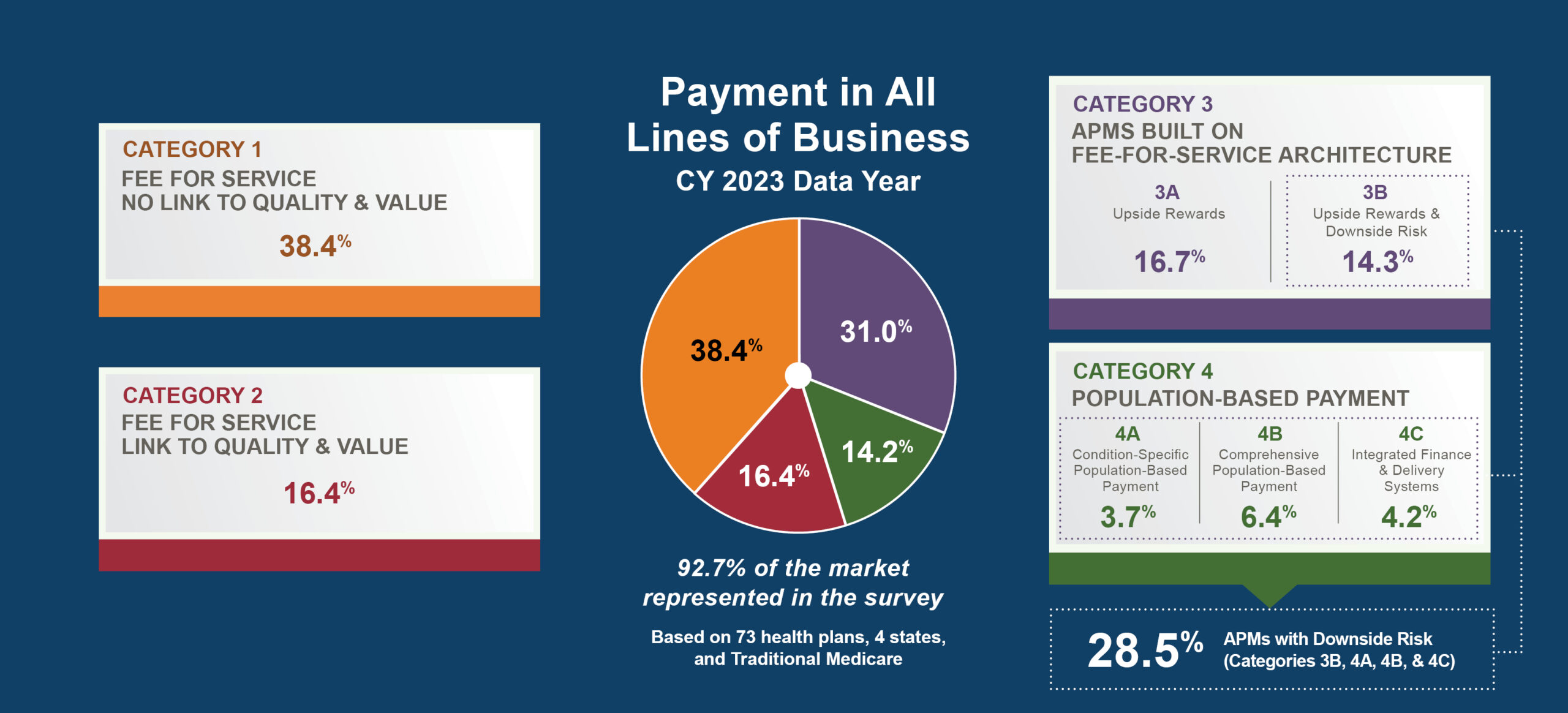

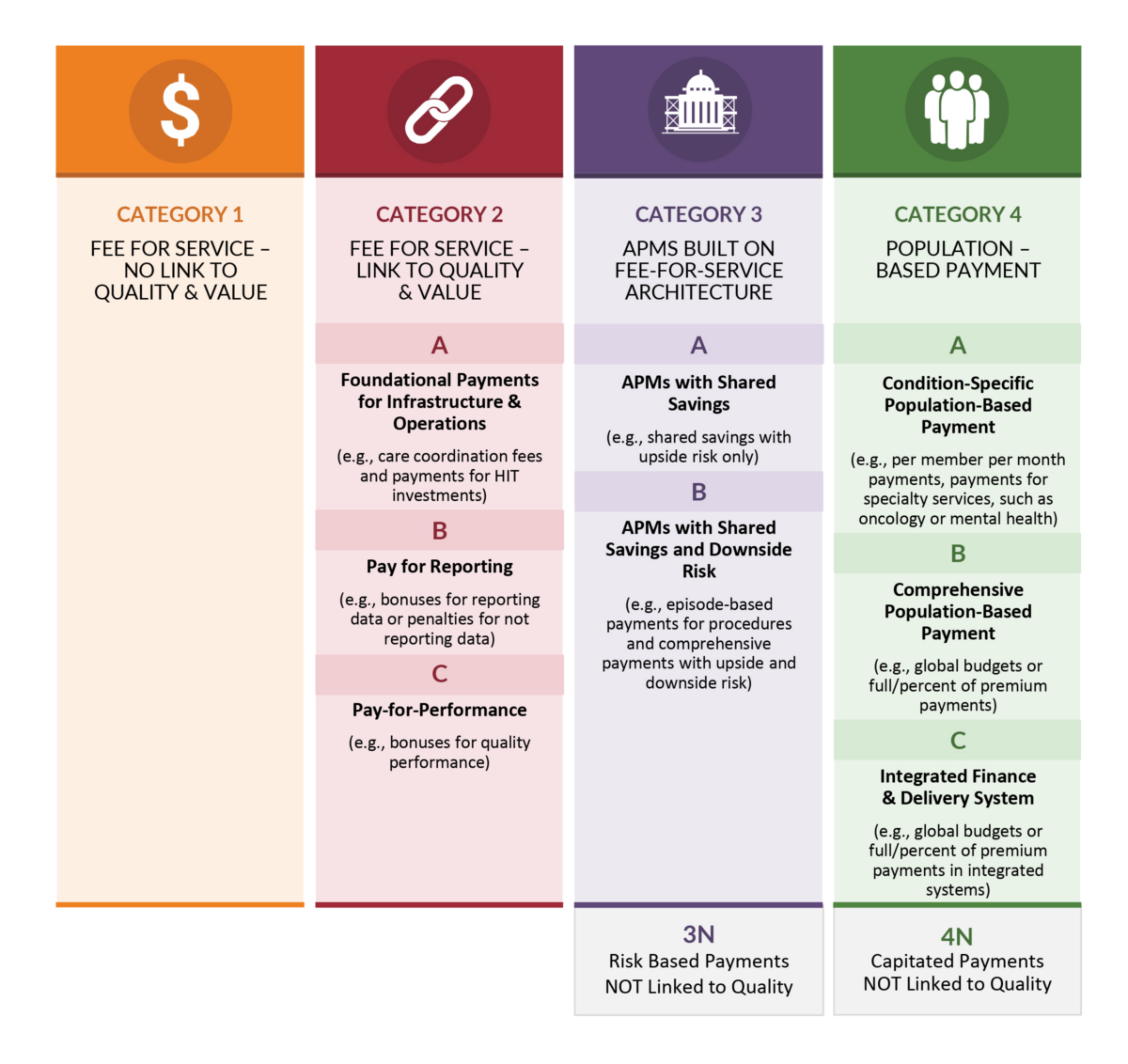

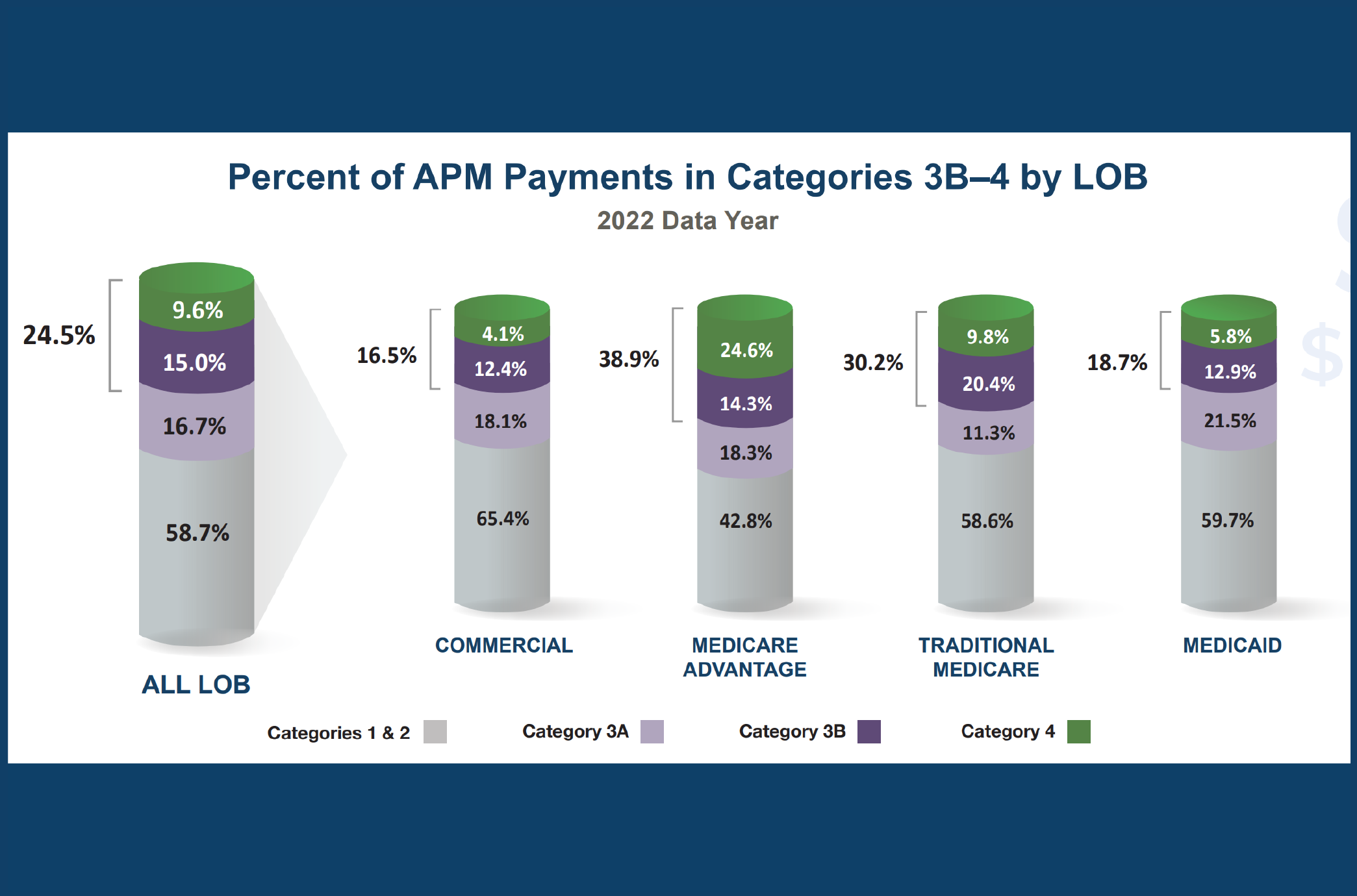

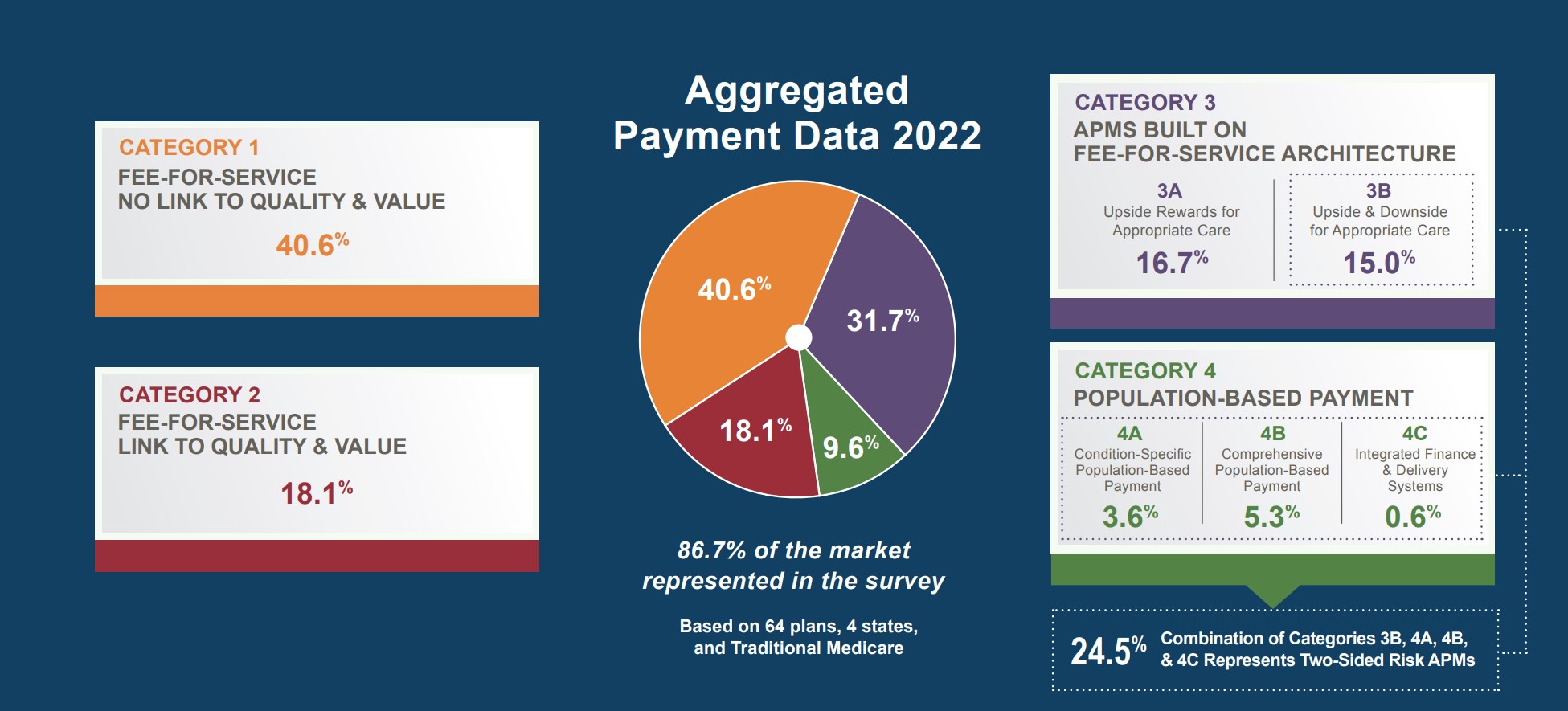

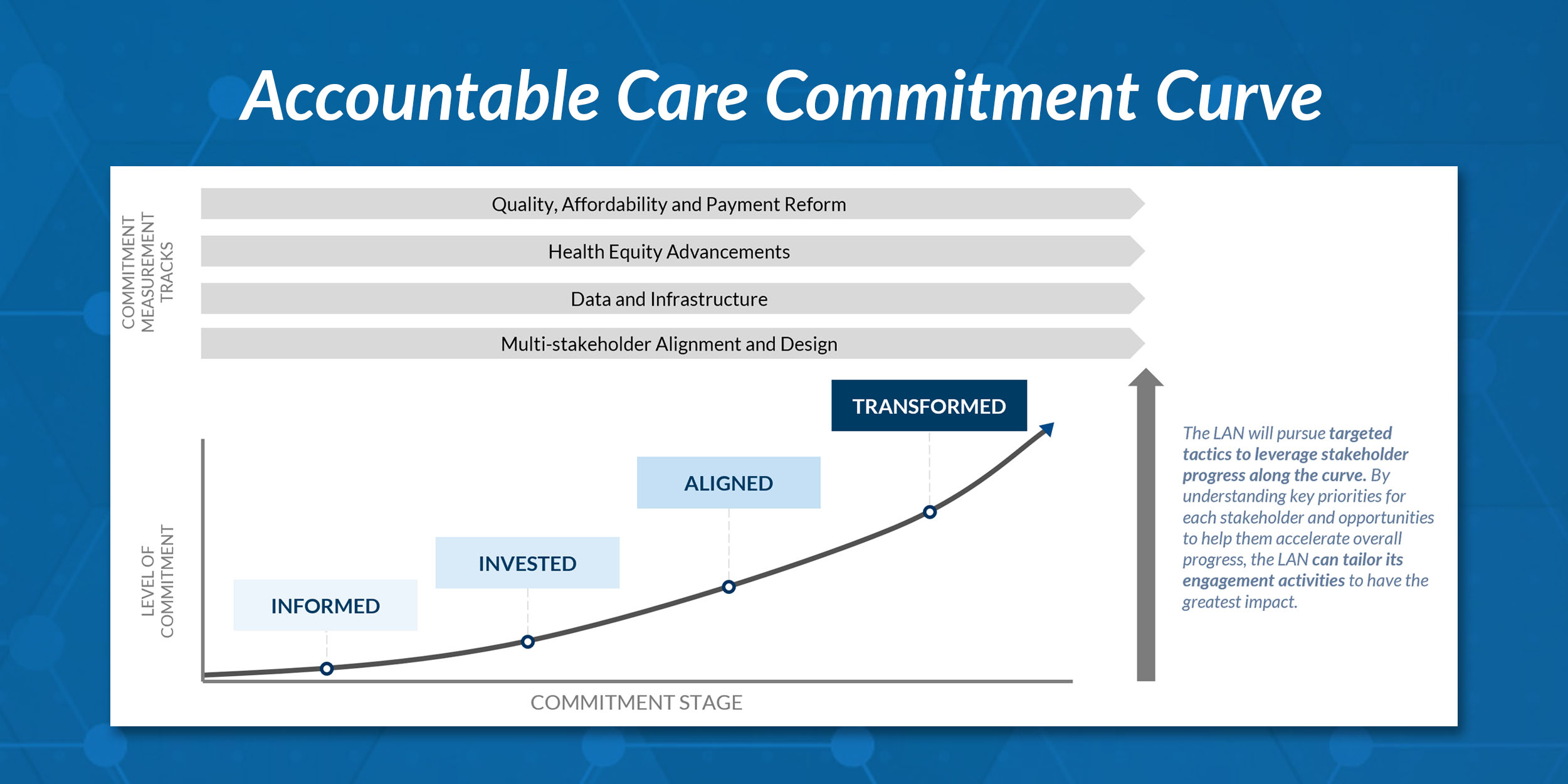

As a result of improved care coordination, all-cause hospital admissions dropped significantly and the cost of care for Medicare patients dropped 7% in year one and 5% in year two. A participating Medicare Advantage plan saved 15% over two years, and Blue Cross Blue Shield also experienced significant cost reductions. Savings were sufficient to trigger incentive payments to providers who met quality targets. As of October 2015, the initiative had saved Medicare $10.8 million over two years. This would not have been possible without a forum fostering stakeholder collaboration and community-wide data sharing. This kind of data sharing can enable the population-based payments in Categories 3 and 4 of the APM Framework.

New Ways to Think About Data

To support population payment and meaningful measurement, we need data. A value-based payment system requires major changes in how providers access and use data, and how purchasers and consumers use the information to purchase care. Physicians need data to model and test new payment approaches and to understand their own performance. Providers cannot be expected to take on risk without the information needed to successfully manage that risk. Population-based alternative payment models, found in Categories 3 and 4 of the LAN’s APM Framework, will require data sharing by payers and providers. Shared data will not only enable providers to manage populations, it will also enable population level measurement. If providers have the information to manage populations and purchasers have information to evaluate outcomes and total cost of care, we can potentially move past the current burdensome cacophony of measures to high-level outcomes that reflect shared values.

CMS has recognized the need for shared, all-payer data and transparency and has taken the lead in enabling regional data use through the Qualified Entity program. Local relationships informed by shared, trusted, transparent data are essential for implementing the changes required in MACRA and payment reform generally. Our member network of regional health improvement collaboratives includes 10 Qualified Entities and has the technical expertise and strong community relationships needed to collect local data and implement national performance measures to meet MACRA requirements while simultaneously working with providers to transform health care regionally and nationally.

We at the Network for Regional Healthcare Improvement (NRHI) believe national payment reform cannot be mandated or summarily required. Payment reform has to enable and support physicians to do what they want to do, need to do, and know how to do. Payment remains a major barrier to physicians doing the right thing for their patients and their communities. Payment change has to enable systems, structures, and practices that enable optimal care. It will take multi-stakeholder leadership, direct engagement, implementation support, and real-world experience to inform our solutions. It may seem counter-intuitive to drive national payment reform from the ground-up, but there is no other way to engineer the comprehensive conversion from a fee-for-service treadmill payment system to one that uses data, performance information, and patient engagement than through a regional multi-stakeholder approach.

With all stakeholders at the table, regional health improvement collaboratives are building the regional infrastructures to supply the information needed to identify and pay for high-value care, and they are enabling stakeholders to use the information to change. The strength of a national network of regional collaboratives is its ability to share information, technology, and lessons from the field. Collaboration within and across regions results in cost savings, expanded access to technical expertise, and the ability to accelerate improvement to deliver high-value care to communities across the United States.

Please note that guest blogs from Guiding Committee and Work Group members represent the views of the individual authors and do not represent official positions of the Guiding Committee, Work Groups, CAMH, or CMS.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models. Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices.

Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices. Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System.

Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System. Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities.

Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities. Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.