Driving Improvements in Primary Care Payments

- September 14, 2016

- Posted by: Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network

- Categories: Interview, LAN Update, Participant Spotlight Interview

Driving Improvements in Primary Care Payments

A Q&A with Rishi Manchanda, Primary Care Payment Model Work Group Member

The LAN recently spoke with Rishi Manchanda, chief medical officer of The Wonderful Company and member of the PCPM Work Group, to offer a purchaser perspective on how cultivating primary care delivery best practices can drive value and improve health outcomes. In this interview, Manchanda also shares his vision for ensuring providers are empowered to make smart decisions when it comes to writing prescriptions, making referrals, and ordering tests. This interview is the second in a short series that explores the role primary care payment can play in health care payment reform efforts:

My hope is that PCPM work will help pave the path to achieving LAN goals by helping primary care providers and purchasers better define “value.” Among other efforts, this means enumerating the key functions that “best-in-class” care delivery models can use to drive better outcomes and value (e.g. demonstrated ability to consider cost, quality and value in clinical decision-making in the spirit of “choosing wisely.”) Then, we must all work to identify which of these key functions are already performed well in existing primary care practices so they can be optimized and brought to scale. Lastly, we have to be candid about those value-driving functions that are currently missing in primary care practice and provide the necessary incentives and support to bring those to scale. For instance, many private companies now invest in coaching, navigation, risk analytics, and disease management services from third-party vendors, many of whom essentially try to measure, track and improve employees’ mastery of key self-management skills like healthy eating, coping skills, and problem-solving skills to prevent or control disease. They’re buying into the value proposition that quantifiable improvements in self-management skills can yield better outcomes at better value. Many current primary care practices aren’t configured to delivery on that value proposition. Perhaps through this PCPM work, we can spur primary care practices to consider how to leverage the relationships and continuity of care they’ve established with patients to demonstrate how they can measurably improve patients’ mastery of self-management skills.

A priority is to help control total costs of care by reducing pharmaceutical spending. Beyond reforms such as reference-based pricing, one way to do this is by supporting primary care and specialty providers to understand and make wiser choices when it comes to prescriptions (e.g. avoiding unnecessary prescriptions, making the choice of low-cost therapeutic equivalents the default, etc). Primary care reform efforts often include efforts to influence and optimize referral, lab, and radiology practices. We need to consider how payment and care delivery reforms can support providers to be good stewards of medicines as well.

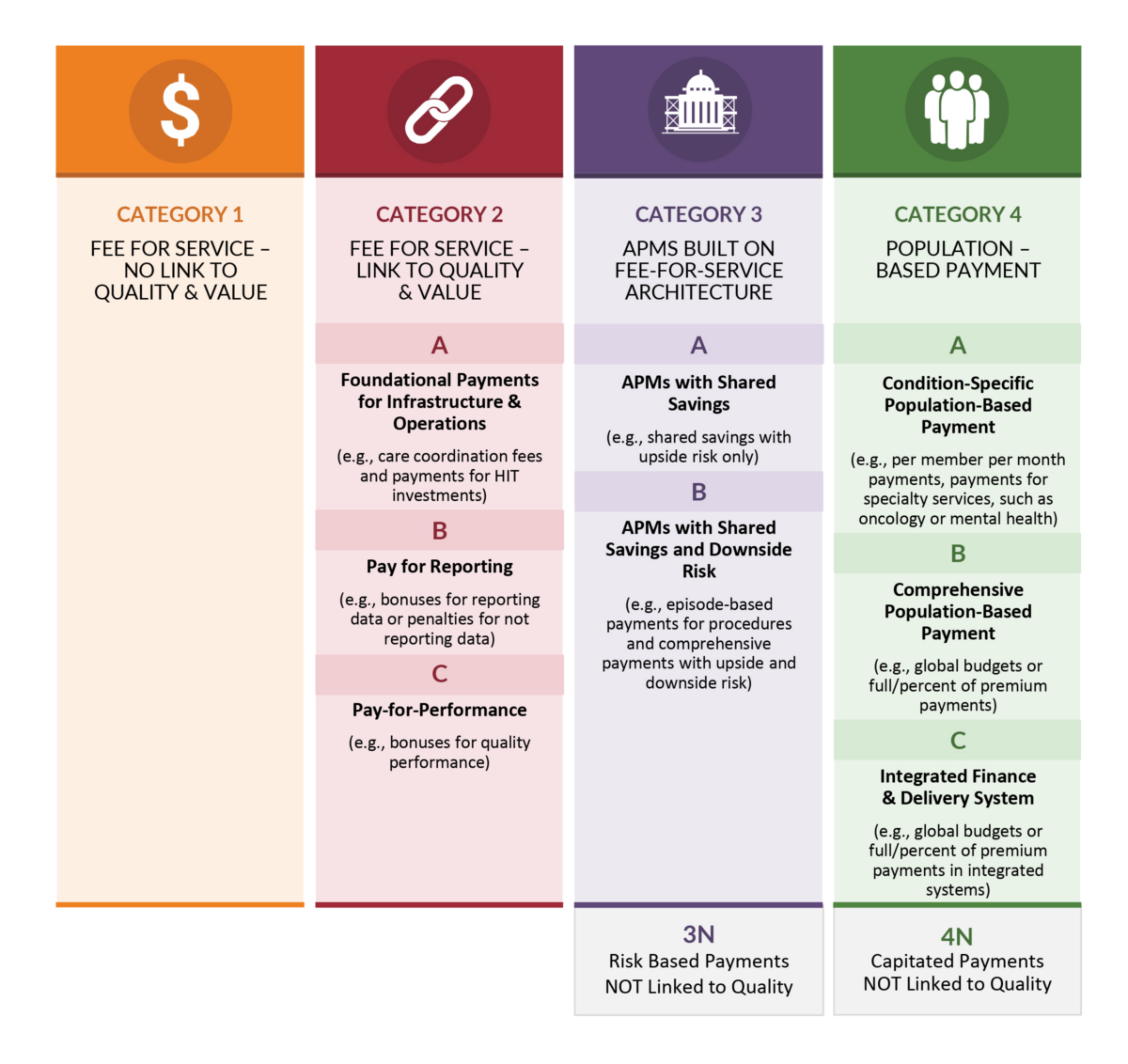

We can’t expect to find a path to better value using volume-based payment models. Different payment models allow us to better understand and design systems that generate better value. I’ve seen first-hand how perverse fee-for-service incentives constrain physician’s ability to provide care in ways that make sense. For instance, I’ve seen primary care practices achieve the Quadruple Aim by applying QI (quality improvement) methods that enable the clinic, along with community partners, to identify and address “upstream” drivers of disease and overutilization among the social determinants of health. Our current volume-based payment models don’t support care redesign experiments like these and others that offer glimpses of better value. That’s why moving to different payment models is so important.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models.

Emily DuHamel Brower, M.B.A., is senior vice president of clinical integration and physician services for Trinity Health. Emphasizing clinical integration and payment model transformation, Ms. Brower provides strategic direction related to the evolving accountable healthcare environment with strong results. Her team is currently accountable for $10.4B of medical expense for 1.6M lives in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid and Commercial Alternative Payment Models. Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices.

Mr. James Sinkoff is the Deputy Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer for Sun River Health (formerly known as Hudson River HealthCare), and the Chief Executive Officer of Solutions 4 Community Health (S4CH); an MSO serving FQHCs and private physician practices. Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System.

Victor is the Chief Medical Officer for TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid Agency. At TennCare, Victor leads the medical office to ensure quality and effective delivery of medical, pharmacy, and dental services to its members. He also leads TennCare’s opioid epidemic strategy, social determinants of health, and practice transformation initiatives across the agency. Prior to joining TennCare, Victor worked at Evolent Health supporting value-based population health care delivery. In 2013, Victor served as a White House Fellow to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Victor completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Emory University still practices clinically as an internist in the Veteran’s Affairs Health System. Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities.

Dr. Brandon G. Wilson, DrPH, MHA (he, him, his) joined Community Catalyst as the Director of the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation, where he leads the Center in bringing the community’s experience to the forefront of health systems transformation and health reform efforts, in order to deliver better care, better value and better health for every community, particularly vulnerable and historically underserved populations. The Center works directly with community advocates around the country to increase the skills and power they have to establish an effective voice at all levels of the health care system. The Center collaborates with innovative health plans, hospitals and providers to incorporate communities and their lived experience into the design of systems of care. The Center also works with state and federal policymakers to spur change that makes the health system more responsive to communities. And it provides consulting services to health plans, provider groups and other health care organizations to help them create meaningful structures for engagement with their communities. Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Tamara Ward is the SVP of Insurance Business Operations at Oscar Health, where she leads the National Network Contracting Strategy and Market Expansion & Readiness. Prior to Oscar she served as VP of Managed Care & Network Operations at TriHealth in Southwest Ohio. With over 15 years of progressive health care experience, she has been instrumental driving collaborative payer provider strategies, improving insurance operations, and building high value networks through her various roles with UHC and other large provider health systems. Her breadth and depth of experience and interest-based approach has allowed her to have success solving some of the most complex issues our industry faces today. Tam is passionate about driving change for marginalized communities, developing Oscar’s Culturally Competent Care Program- reducing healthcare disparities and improving access for the underserved population. Tamara holds a B.A. from the University of Cincinnati’s and M.B.A from Miami University.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.

Dr. Peter Walsh joined the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing as the Chief Medical Officer on December 1, 2020. Prior to joining HCPF, Dr. Walsh served as a Hospital Field Representative/Surveyor at the Joint Commission, headquartered in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois.